My Art History Self-Study: Art Visions and Ideals that Shaped the Harlem Renaissance

This essay is part of my ongoing effort to study art history as a way to learn, reflect, and share what I discover.

Back in early August, I picked up When Harlem Was in Vogue (1979) by David Levering Lewis at a secondhand bookstore in Paris. Lewis, a former professor at Howard and NYU and a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner, is a brilliant historian.

I devoured the book on long train rides and park benches around Paris. It offered perspectives on the Harlem Renaissance that I hadn’t encountered before.

The first revelation was that the Harlem Renaissance wasn’t spontaneous. It was intentionally coordinated by a small group of upper- and middle-class Black intellectuals, led by W. E. B. Du Bois and Alain Locke.

The second realization is that both men had similar but slightly different views on what kind of art Black artists in the 1920s and 1930s should make.

They both believed art could challenge entrenched stereotypes of Black Americans but their views reflected different values about how art should serve that goal.

Du Bois valued art that only served social and political purposes. In a speech he said, “I don’t give a damn for art unless it’s pushing Black people forward.”

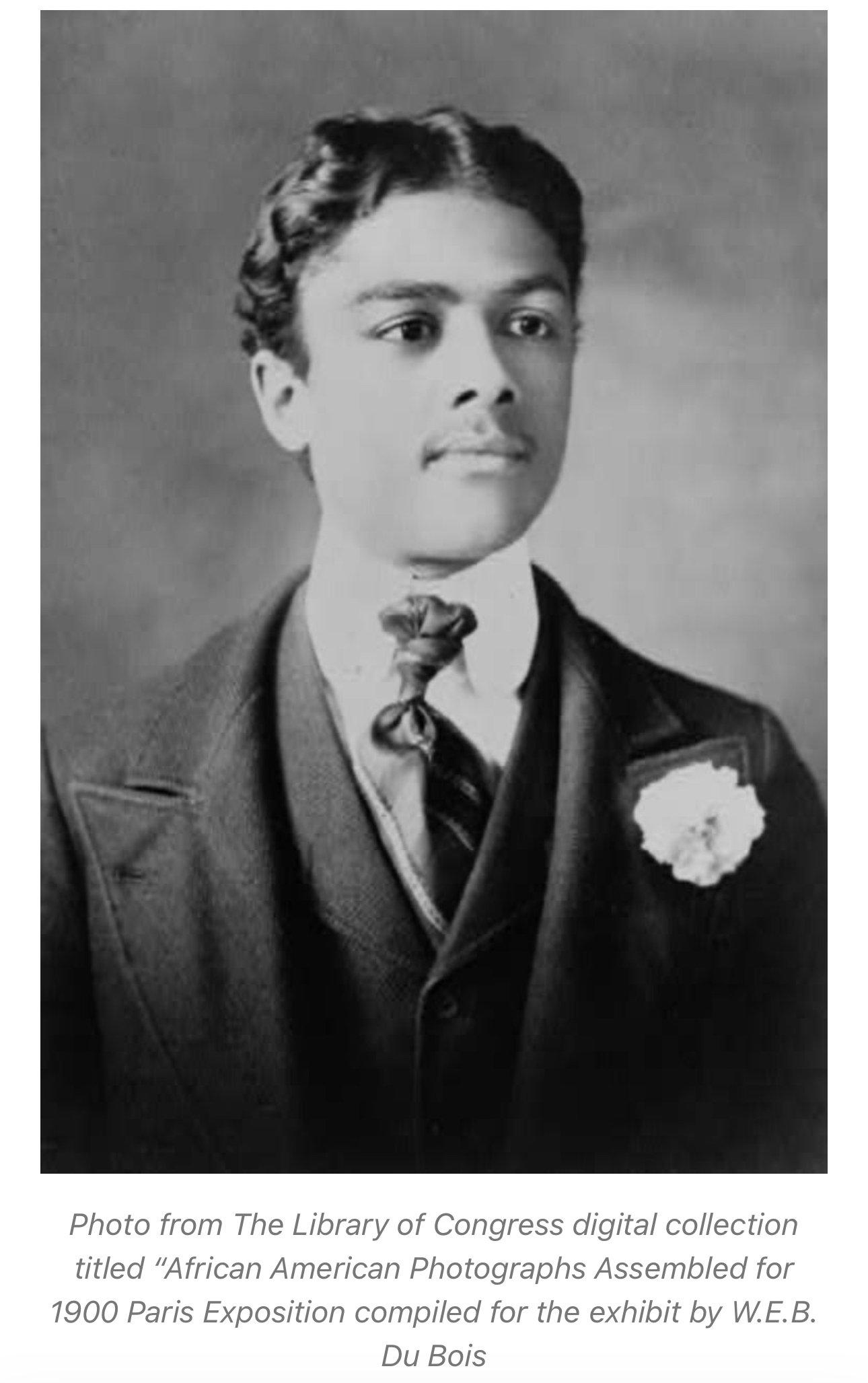

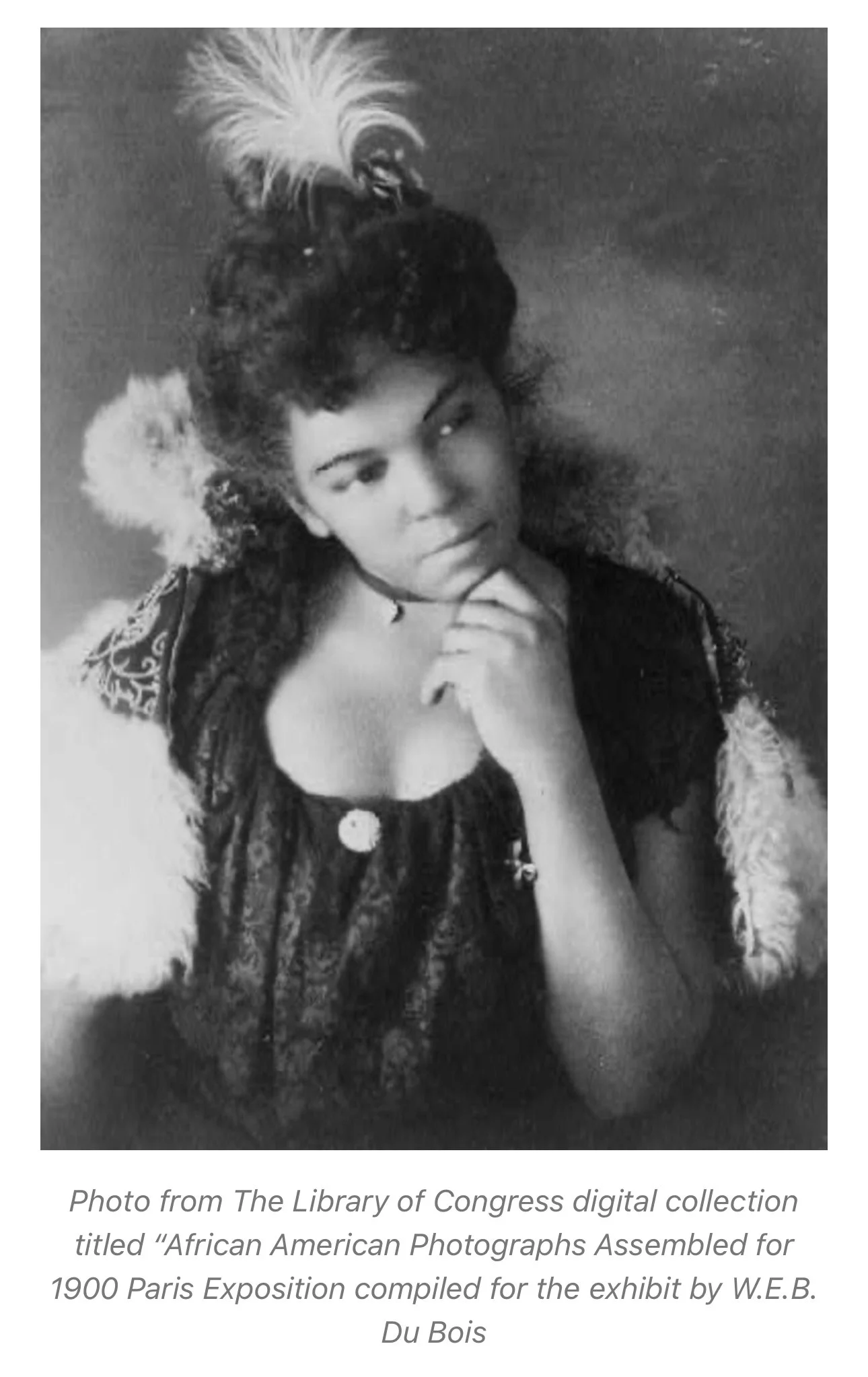

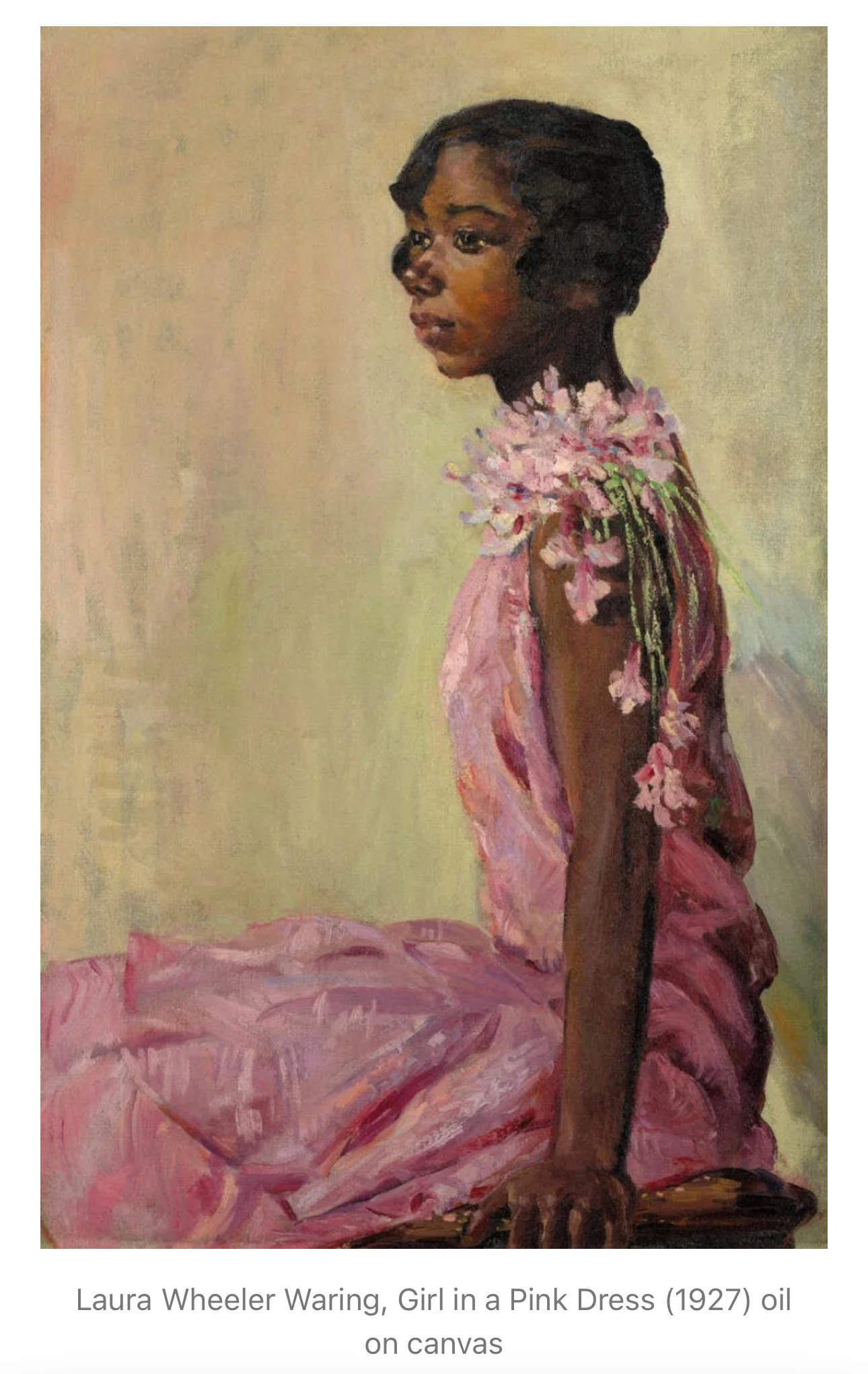

He wanted all art whether it be visual, literature, poetry, plays or music to communicate intelligence and achievements of Black Americans. Think mostly portraits, prim and proper, not a hair out of place art that conveyed gravitas, writings that showed intellect, scholarship, orchestra symphonies instead of ragtime Jazz.

This often put him at odds with other artists and writers of the time. Zora Neale Hurston, for example, mocked Du Bois and his circle for what she saw as their high-brow, bourgeois, respectability-focused approach to Black art. If you’ve read Hurston’s work, you know she liked to write without pretension.

Locke, meanwhile valued artistic freedom and saw realness and individual expression as a better way to expand how Black life was seen. He was more interested in art that portrayed everyday Black life—people playing cards, documenting the conditions of Black people migrating north, or artistic play with African forms and aesthetics.

In The New Negro (1925) and later essays, he argued that an artist’s first duty was self-expression, not racial uplift.

Locke believed art could shift stereotypes if Black artists created original work that is authentic rather than constantly worrying about the viewer’s approval.

He wanted Black artists to participate fully in the broader modern art conversation, especially at a time when European artists like Henri Matisse were borrowing heavily from African masks, textiles, and design.

Reader, I know Du Bois is coming across as a stick in the mud but context matters.

He had been fighting racist caricatures of Black Americans for decades before the Harlem Renaissance began. In 1895, he became the first African American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard and later studied in Berlin, Germany. I can only imagine the challenges he faced navigating those institutions as the first and only in the late 1800s.

Long before Harlem became the epicenter of Black art, literature and music, Du Bois helped organize The Exhibit of American Negroes for the year 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle.

The U.S. section at the Paris fair excluded African Americans, so Du Bois and others created a separate exhibition to highlight Black life and achievement.

Their goal was to prove through visual, statistical, and artistic data that African Americans had advanced dramatically in education, industry, and culture since Emancipation.

Du Bois and his students at Atlanta University produced more than sixty hand-drawn charts and graphs showing progress in literacy, land ownership, and social institutions. These were paired with photographs of Black Americans designed to counter racist imagery circulating in the U.S. and Europe.

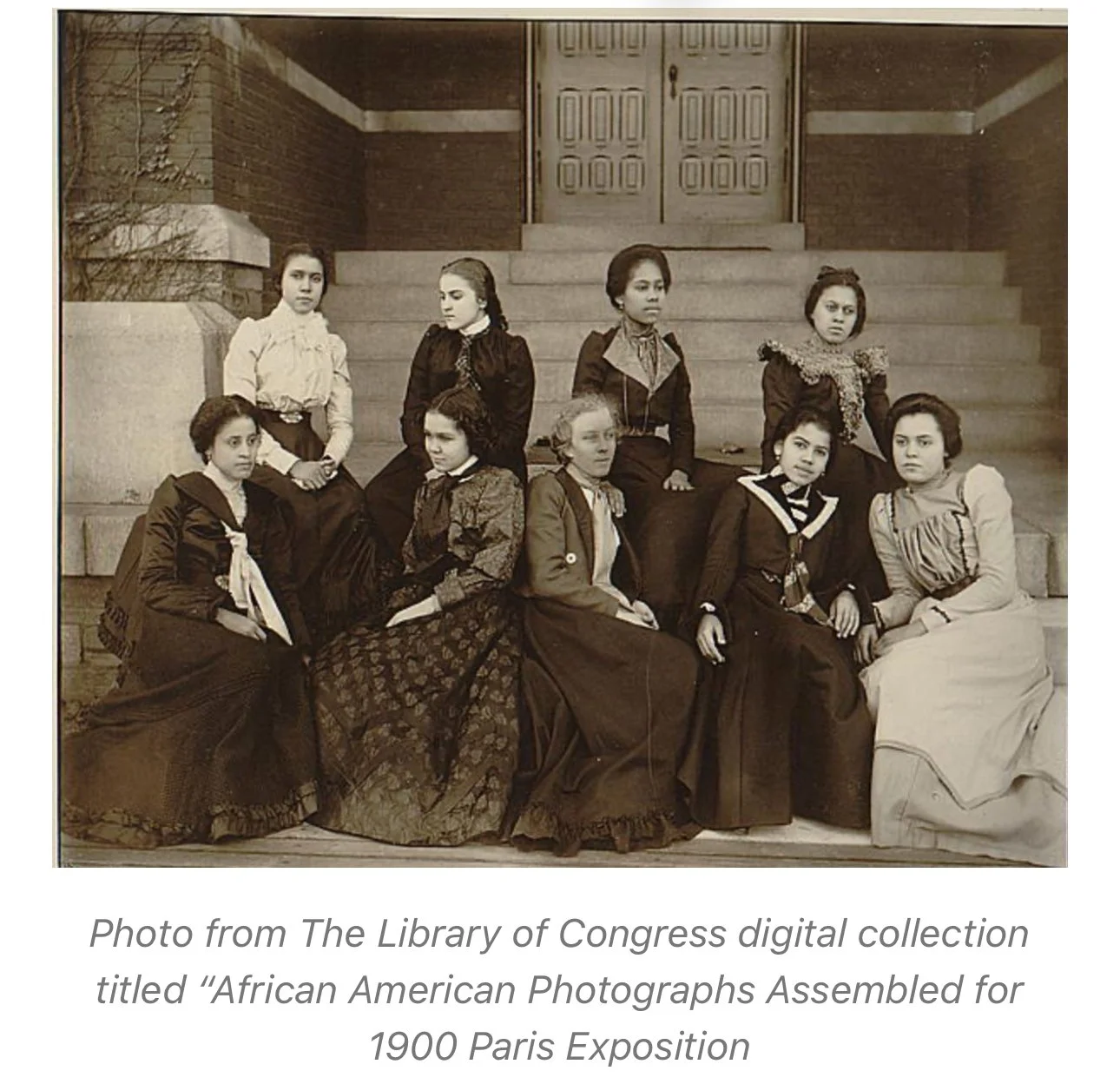

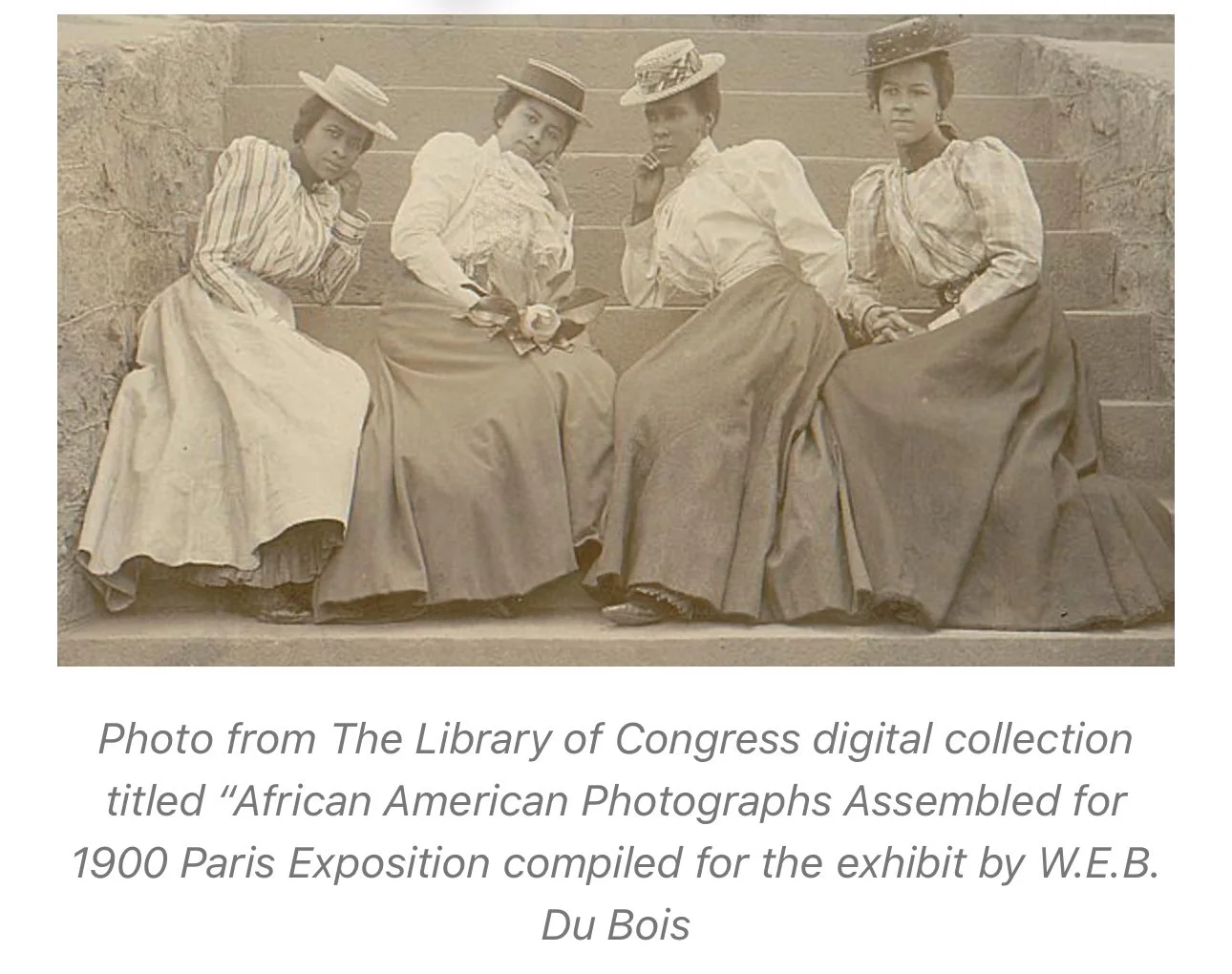

In the images he curated, you can see Du Bois’s vision for how Black people should be portrayed.

The Paris exhibit was one of the earliest moments in American history to present portraits of Black Americans with dignity and grace.

The Exhibit of American Negroes was widely praised by international audiences and judges for its rigor and design. It earned several awards.

The exhibit also helped shape European interest in the intellectual and artistic life of Black America, laying groundwork for many Harlem Renaissance artists decades later to travel and live in Paris. It also drew Europeans straight to Harlem’s jazz clubs and theaters.

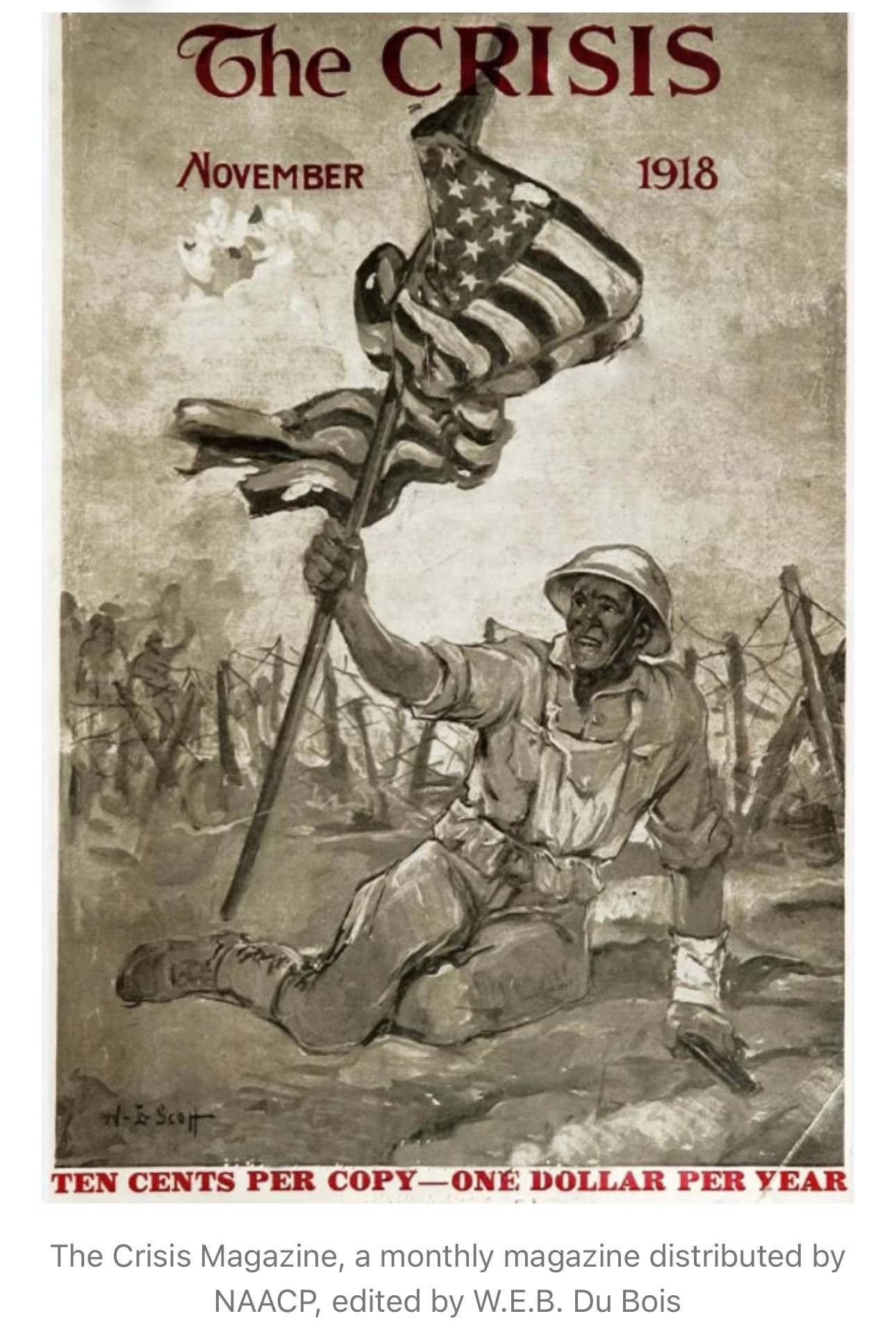

Despite the exhibit’s success, Du Bois returned home to an America where lynchings were common and rent in Harlem was double for Black tenants. He continued his lifelong campaign for equality, becoming editor of The Crisis magazine and a leader of the NAACP, which played a major role in shaping the first phase of the Harlem Renaissance.

Building on that work, Du Bois and Locke helped set in motion what became the Harlem Renaissance.

During those early years, they created files on writers, poets, painters, sculptors, and musicians across the country—many of them students at HBCUs. They actively recruited artists to move to Harlem, often providing stipends, housing, and opportunities to publish or exhibit their work.

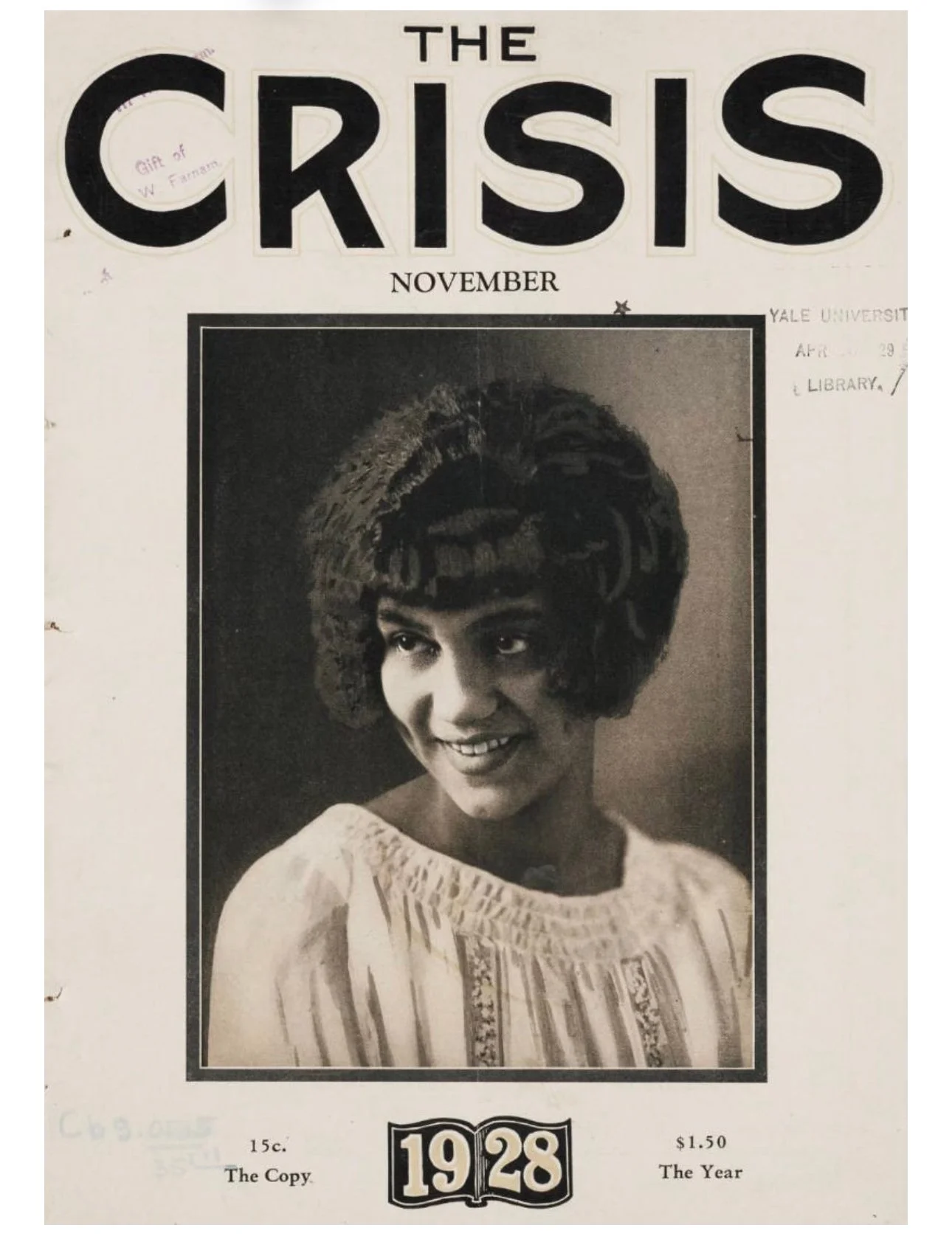

Awards and prizes were created to recognize their contributions, and The Crisis magazine became a central platform for exposure. By 1919, the magazine was selling over 100,000 copies a month.

As Lewis writes,“In an era of rampant illiteracy, when hard labor left Afro Americans little time or inclination for reading Harvard-accented editorials, the magazine found its way into kerosene-lit sharecroppers’ cabin and cramped factory workers’ tenements.” (Levering-Lewis, 1979)

The second phase (1924–1929) was the Harlem Renaissance at its height. Jazz, blues, and theater flourished, and Harlem’s influence spread nationally and internationally during this phase.

Harlem became the cultural capital of Black America, filled with literary and art salons hosted by figures like A’Lelia Walker, daughter of millionaire Madam C. J. Walker.

Writers such as Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and Countee Cullen, along with visual artists like Aaron Douglas and Archibald Motley, helped define modern day literature and visual art. Mind you, before the first phase of the Harlem Renaissance, there were only five books published in the entire United States by Black authors.

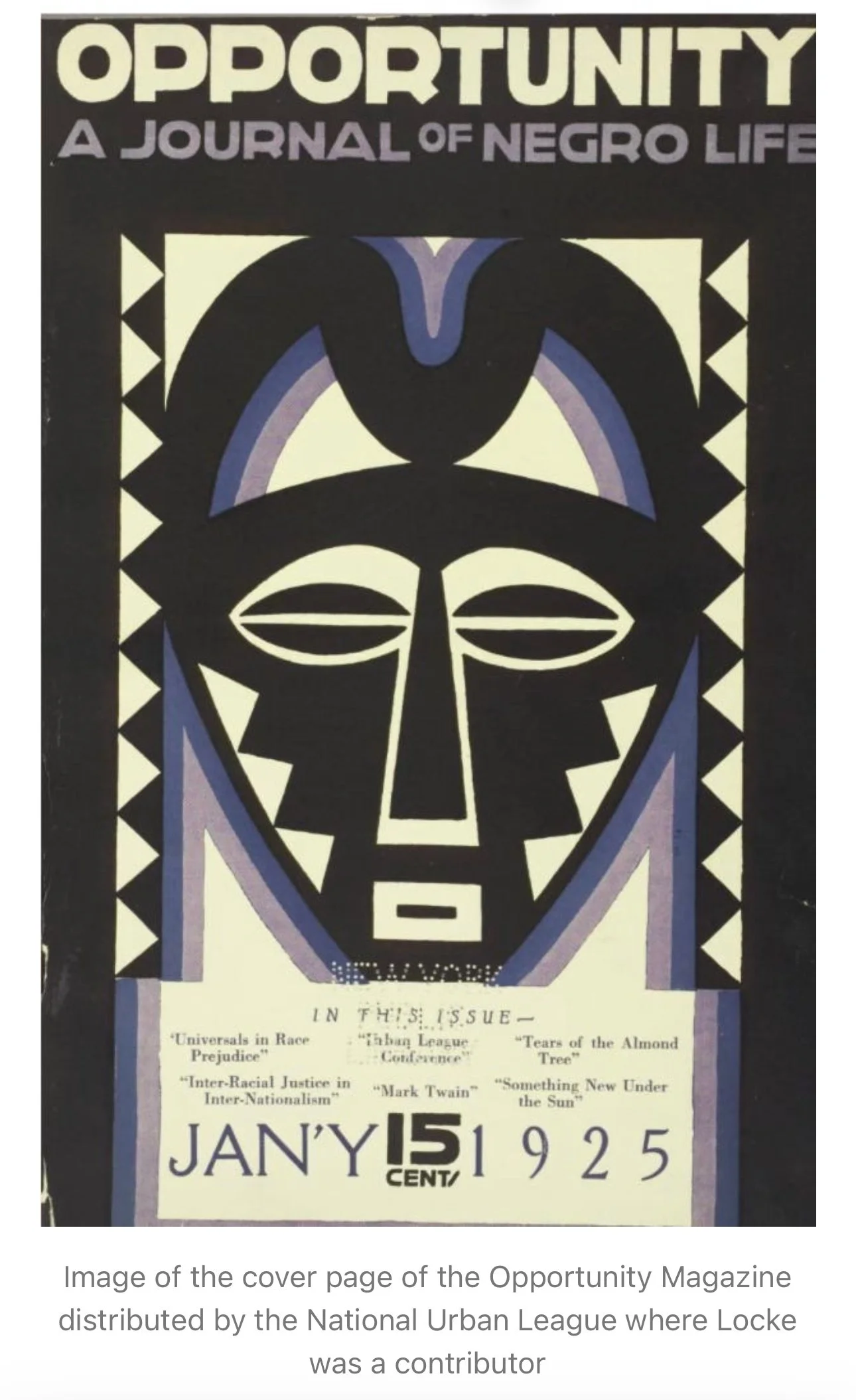

The third phase (1930–mid-1930s) coincided with the Great Depression. Economic collapse dismantled the patronage systems that had supported artists, but Du Bois and Locke continued to champion their work through The Crisis and Opportunity magazines.

Du Bois used The Crisis to show images of Black life, favoring realism and portraiture that reinforced dignity instead of avant-garde art that risked feeding racist perceptions.

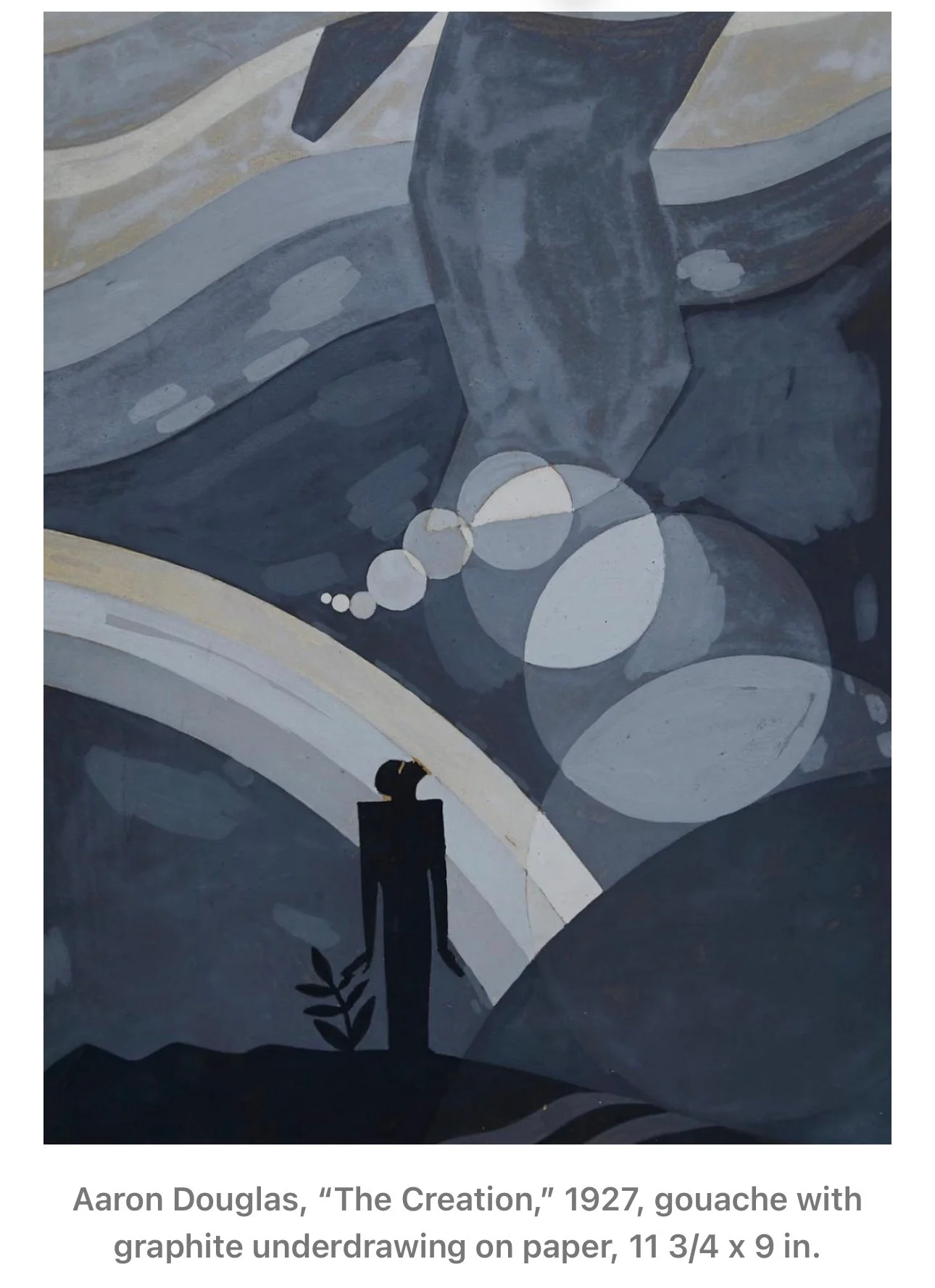

I got curious about what this meant in practice, so I researched artists Du Bois featured or commissioned. Aaron Douglas (b. 1899), often called “the father of Black American art,” was one of them. He illustrated covers for The Crisis and later for Locke’s The New Negro after being urged by Du Bois to quit his teaching job in Missouri and move to Harlem in 1924.

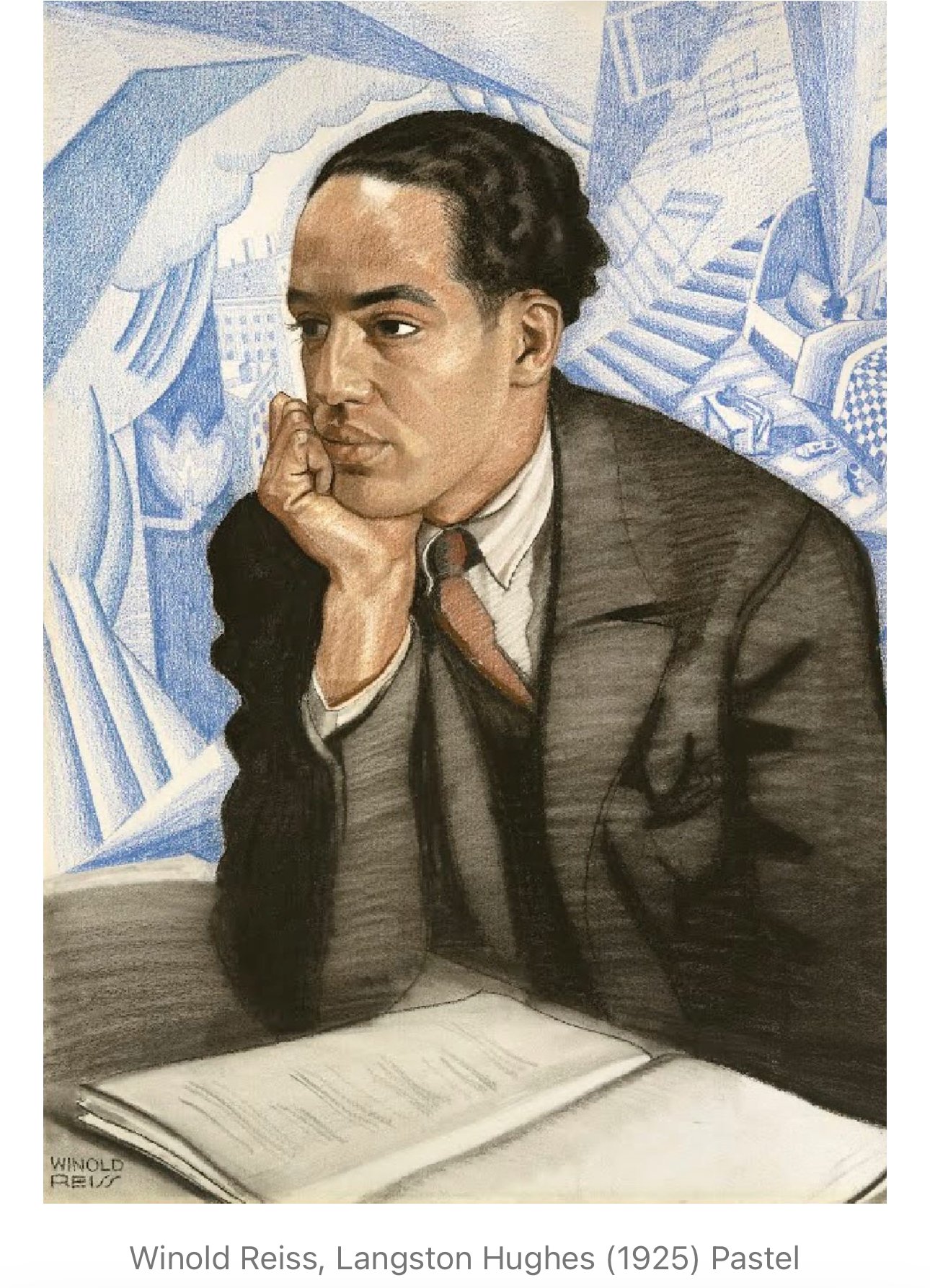

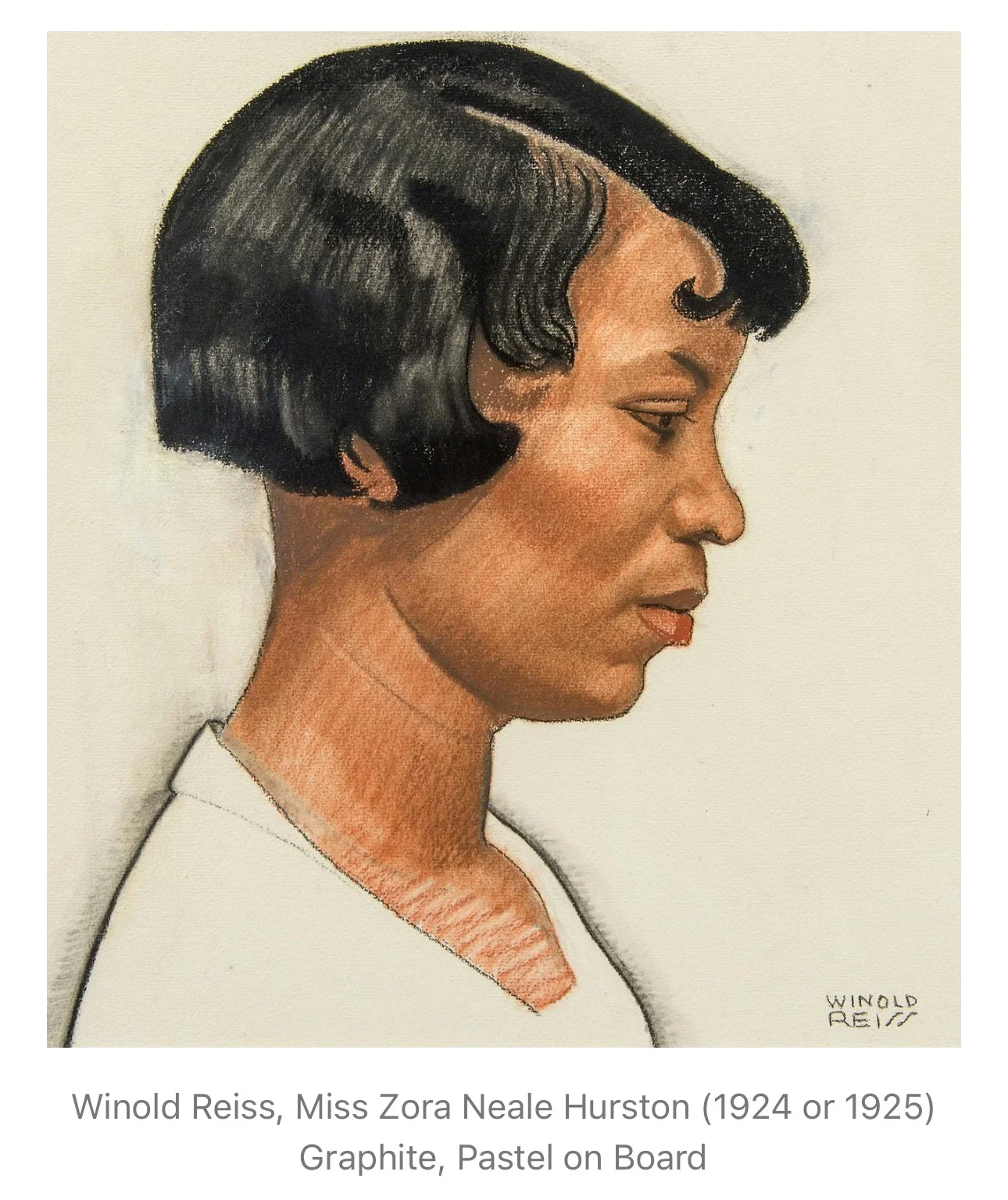

Another artist Du Bois commissioned was Winold Reiss, a white German-born modernist who collaborated with both Du Bois and Locke. Reiss’s created portraits of Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston in a graceful way. He also gave lessons to several young Harlem artists.

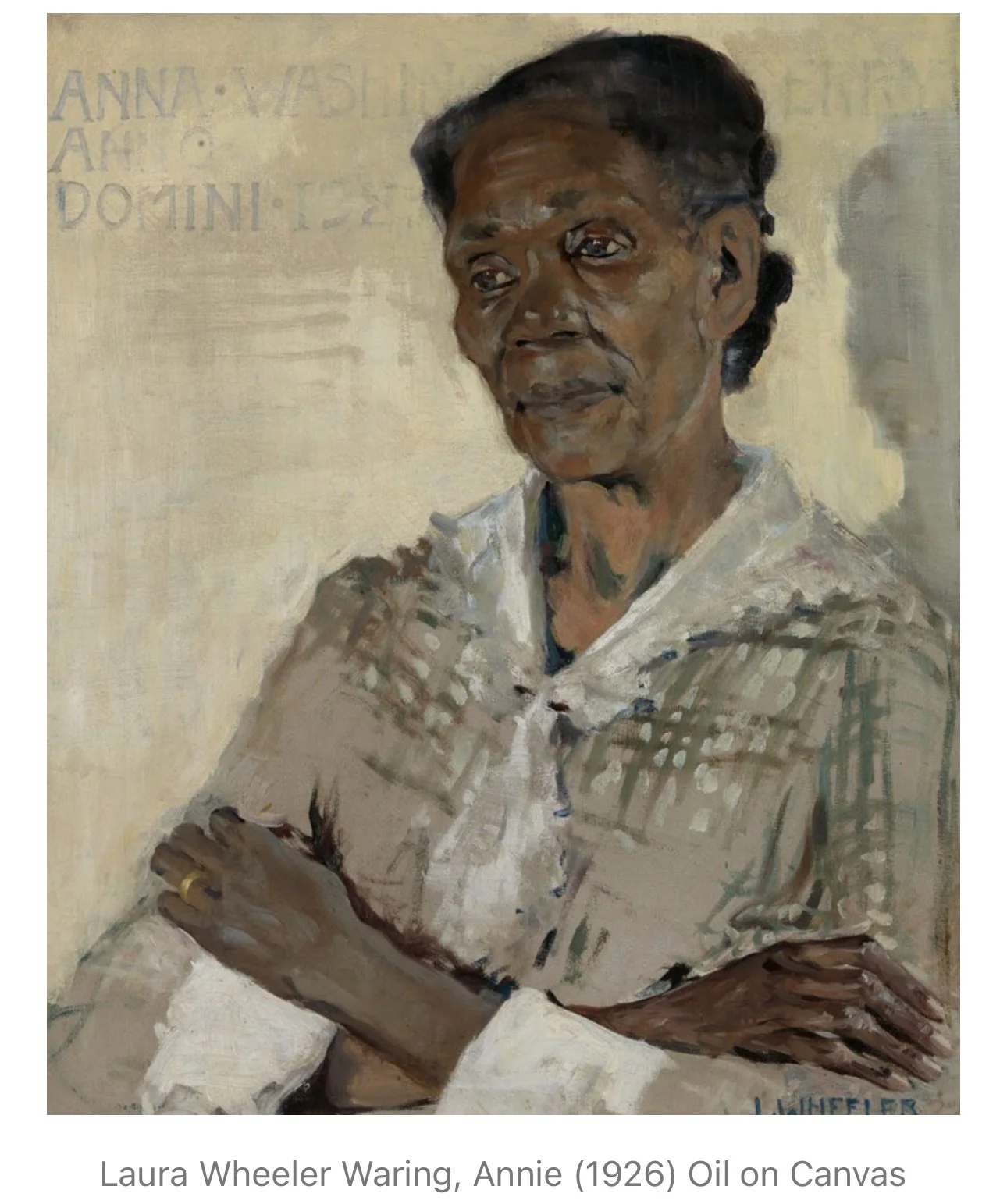

Laura Wheeler Waring (b. 1887) was another frequent Crisis contributor, known for portraits of prominent African Americans. Her 1925 portrait of laundress Annie Washington Derry, painted in muted browns and beiges, was exhibited in Paris and across the U.S. and became one the defining work of her career.

Where Du Bois sought to prove equal footing through art that said, “We are just like you,” Locke wanted to show that Black art was powerful precisely because of its difference—its originality and connection to African aesthetics.

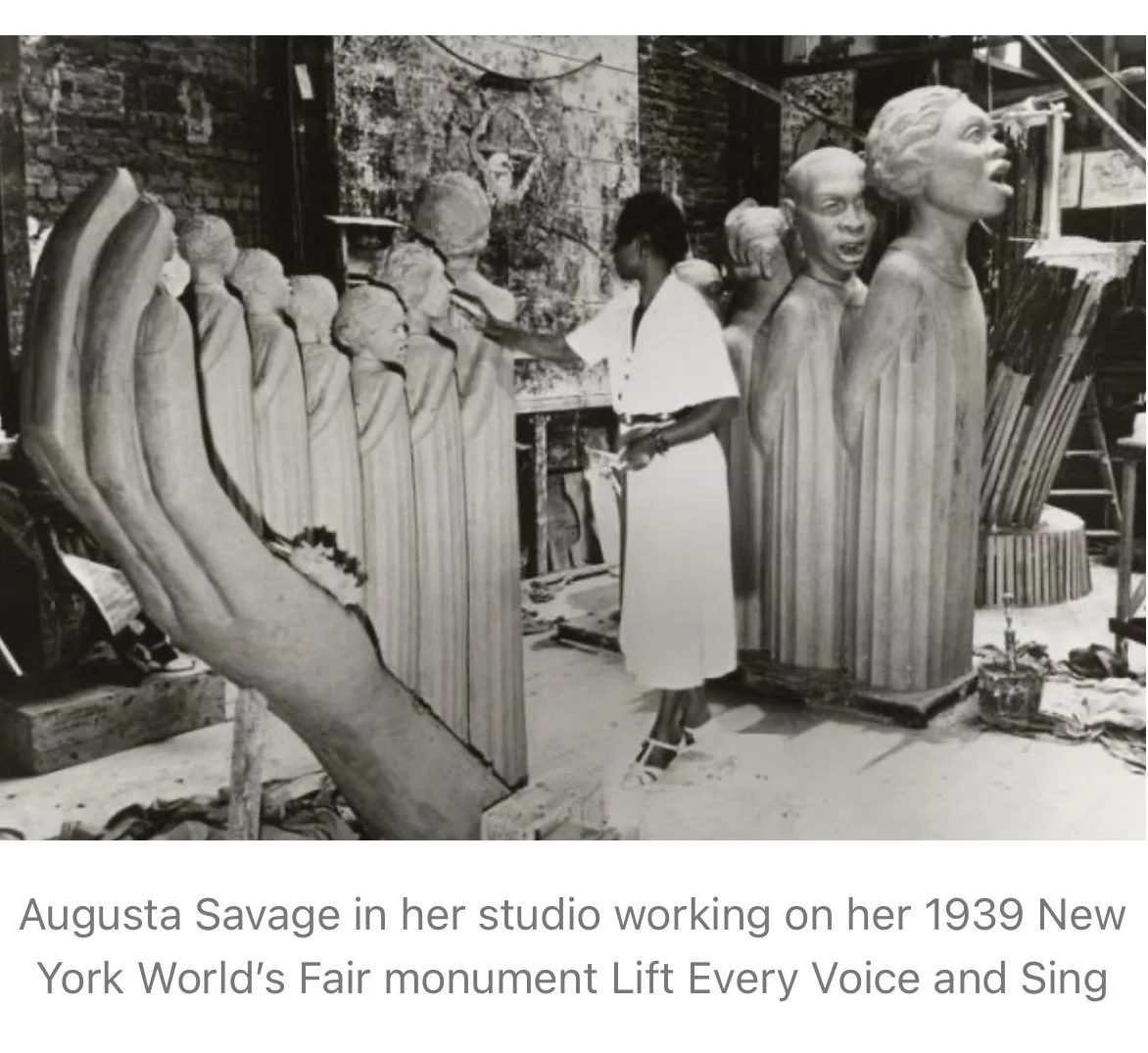

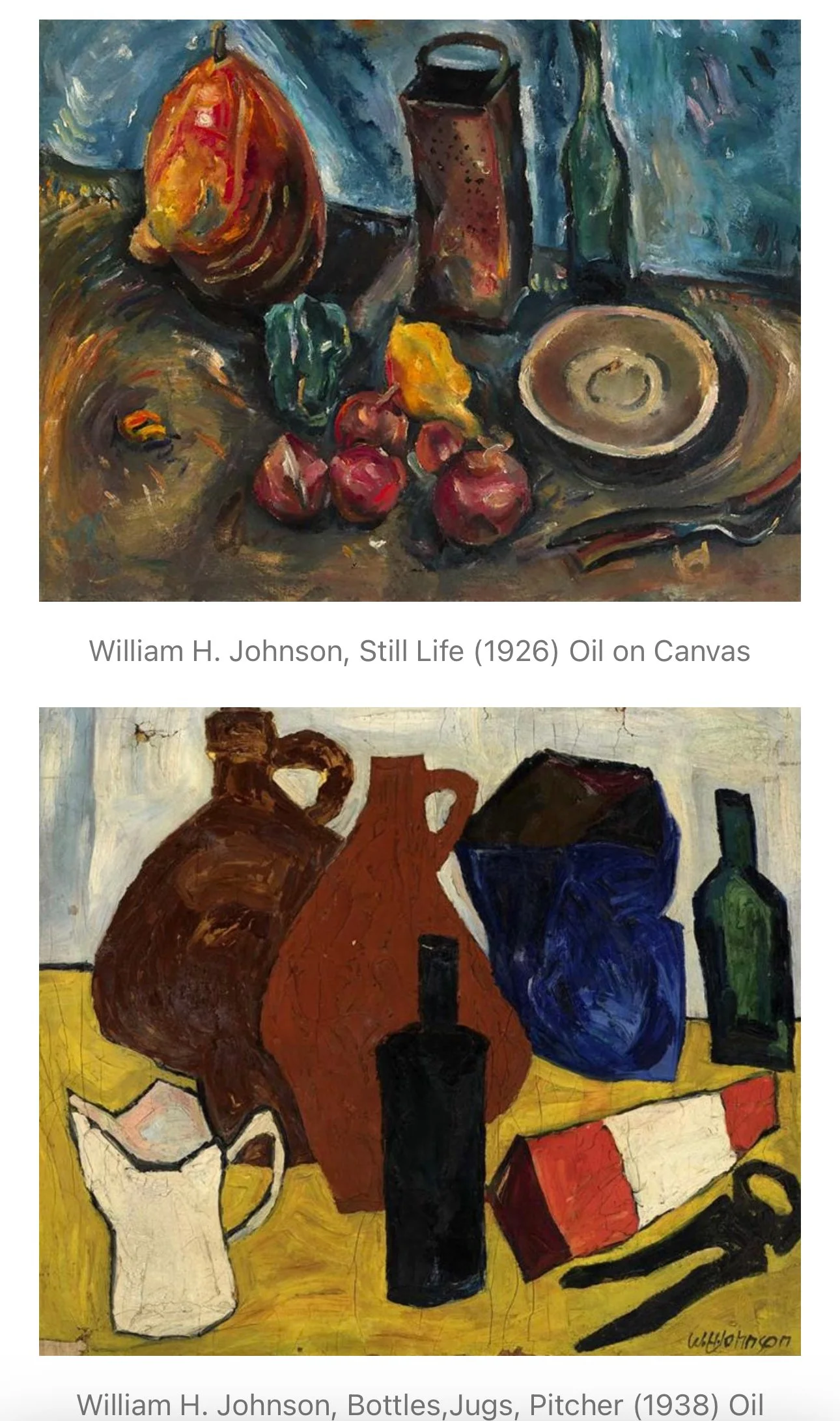

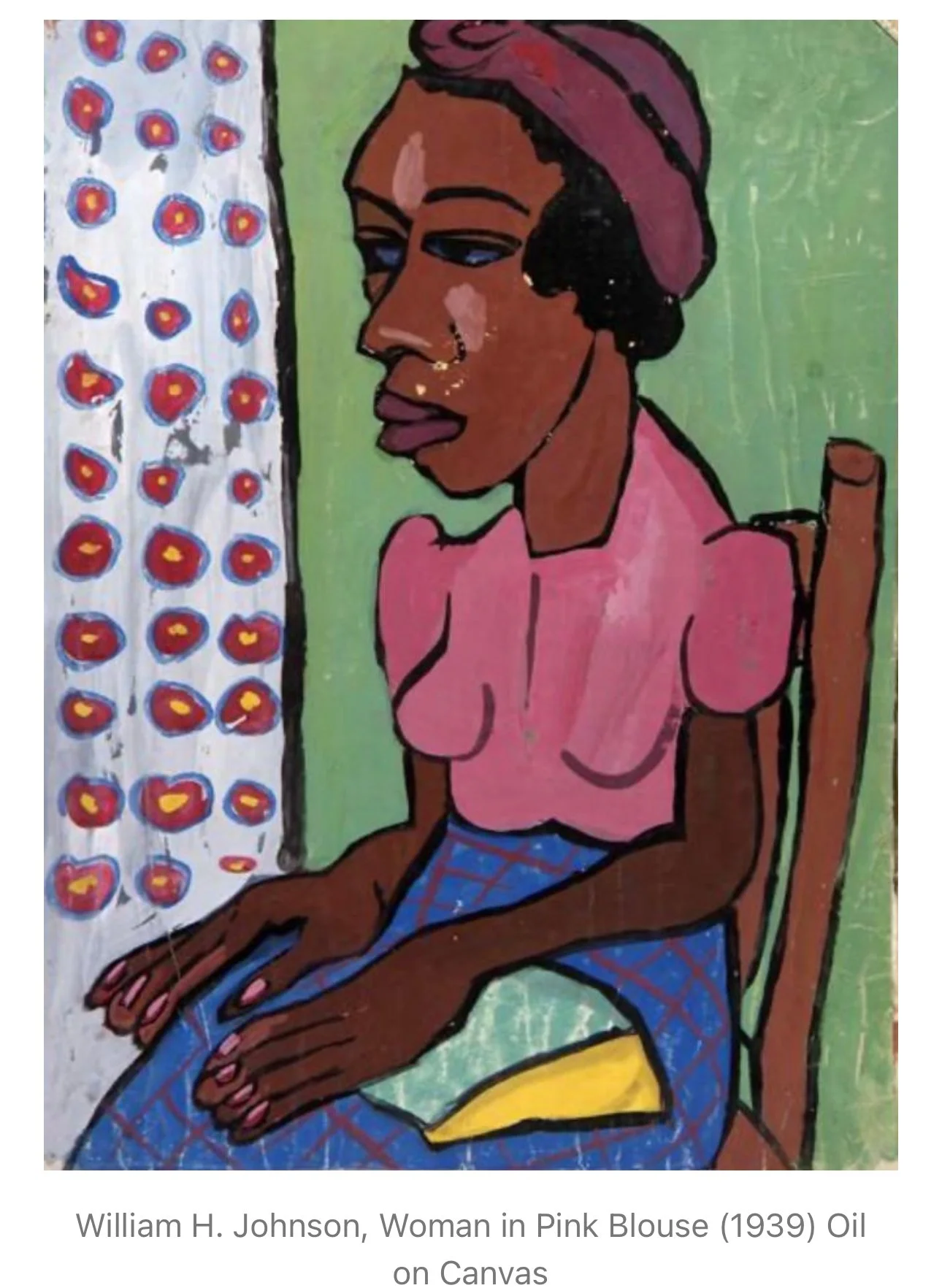

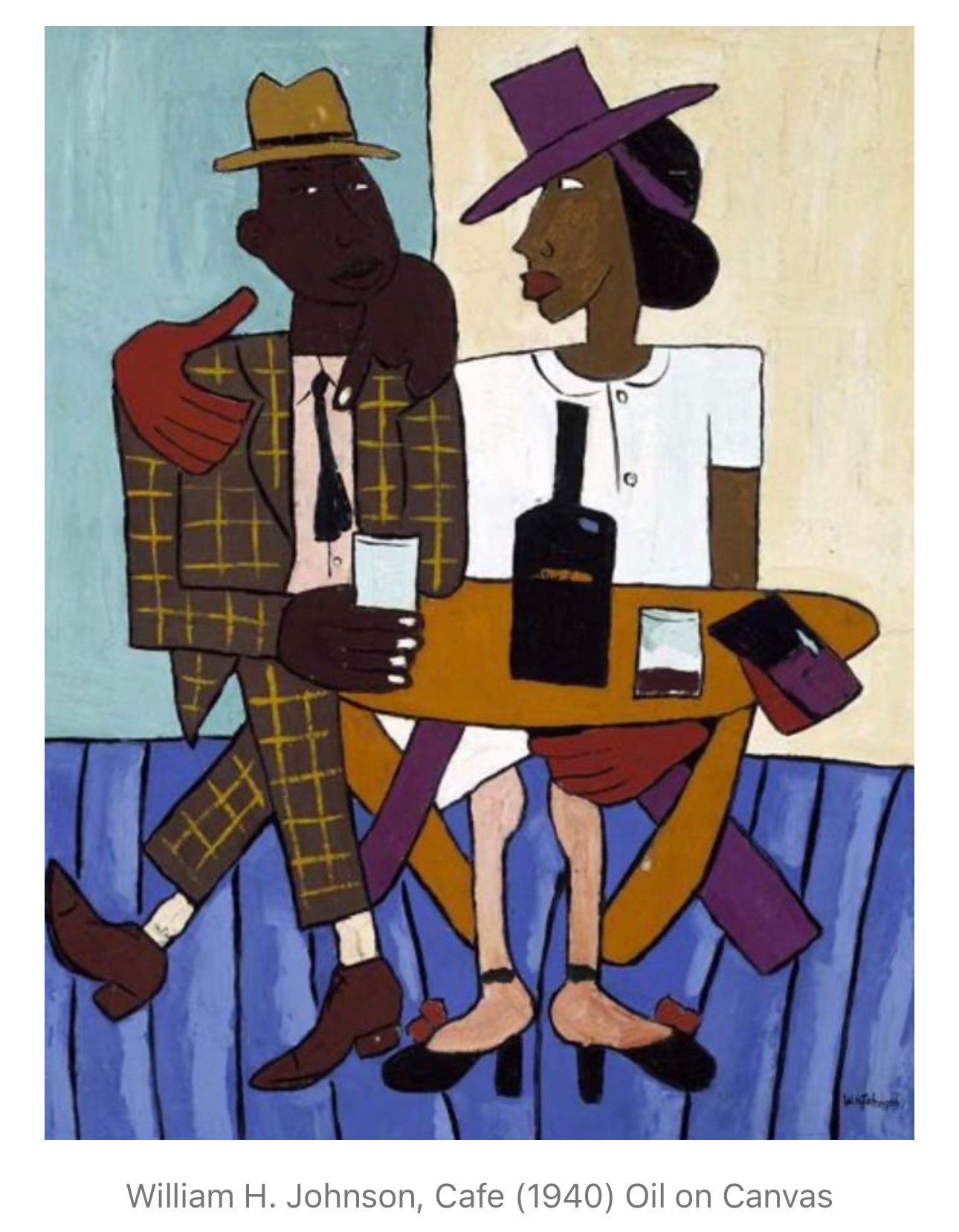

Among the artists Locke supported through Opportunity magazine and his curatorial work were Augusta Savage, William H. Johnson, James Lesesne Wells, and Hale Woodruff, all of whom sought originality and self-expression in their art.

William H. Johnson’s work really stands out for me and my favorite to see when I visit the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC. He moved to France in 1926 and really delved into modernism specifically fauvism and cubism.

After reading about Du Bois and Locke’s philosophies, I kept thinking about how their ideas continue to live in the work of contemporary artists. When I saw Amy Sherald’s paintings at the Whitney Museum in New York earlier this year, I couldn’t help but feel that her portraits center Black subjects in a way Du Bois might have approved of.

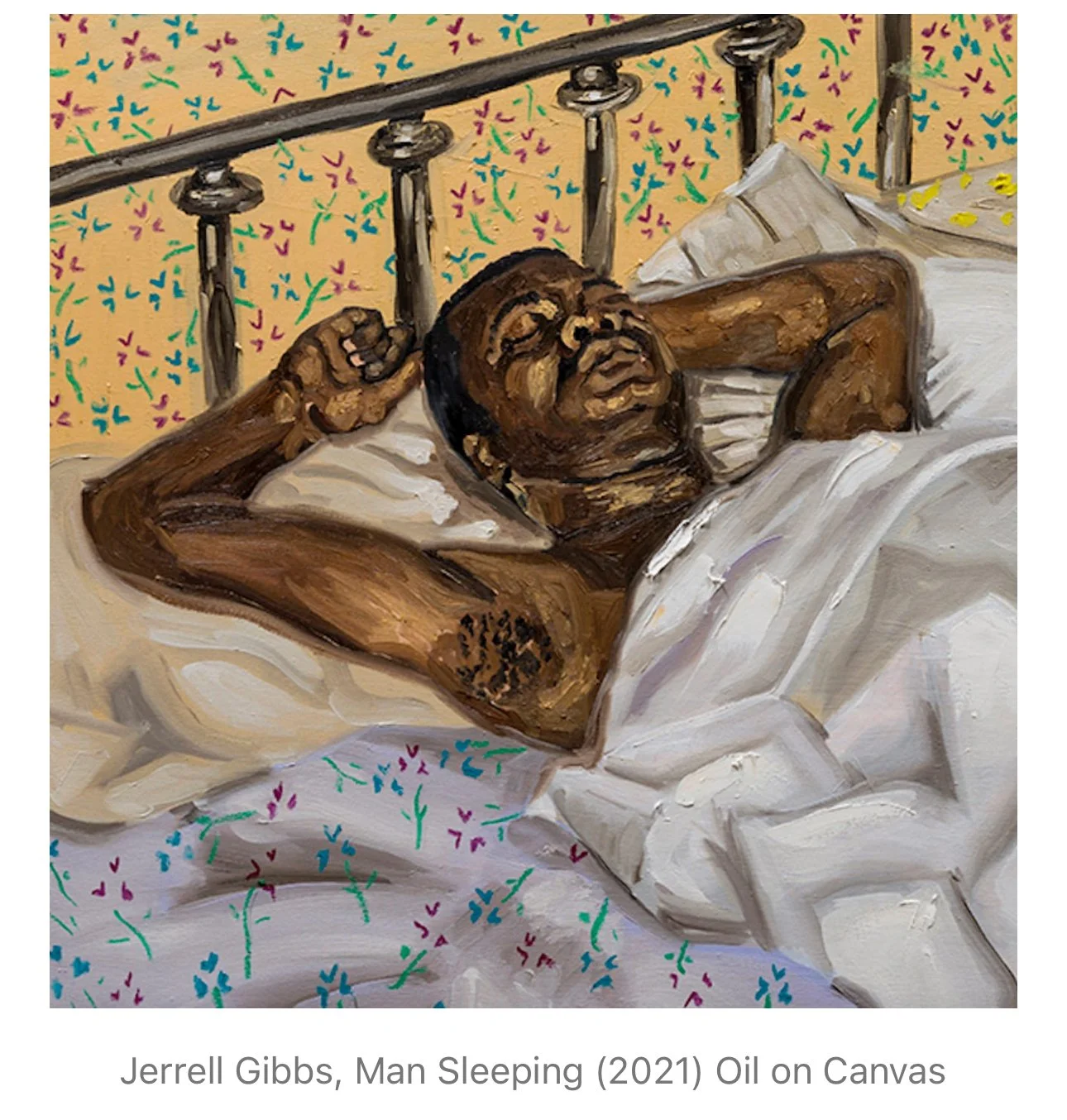

Jerrell Gibbs paints from family photographs, capturing the intimacy of everyday Black life. His work feels in line with what I imagine Locke admired.

What I find especially interesting is how much of contemporary Black art still revolves around portraiture. There’s far less emphasis on still lifes, landscapes, or pure abstraction. It makes me wonder if that imbalance comes from a continued need to push for more visibility and respect for the Black figure. It’s another reminder that Du Bois and Locke’s aesthetic debates are still alive more than a hundred years later.