Writer Ralph Ellison’s Photography

As I dig deeper into art history, I’ve noticed how sparse the documentation is for Black visual artists from that era. We can name a slew of Black writers and musicians, but visual artists? Much fewer. So it was especially exciting to learn that writer and essayist Ralph Ellison was double dipping—writing and photography.

Ralph Ellison swam in the same creative Harlem waters as figures like Richard Wright, Langston Hughes, and Zora Neale Hurston during the Harlem Renaissance.

Born in 1913 in Oklahoma City, Ellison’s father named him “Ralph Waldo” after the writer Ralph Waldo Emerson in hopes that his son would also become a writer. Ellison fulfilled his Dad’s vision with his 1952 novel Invisible Man, a deeply resonate work that explores race, identity, and what it means to be unseen in America.

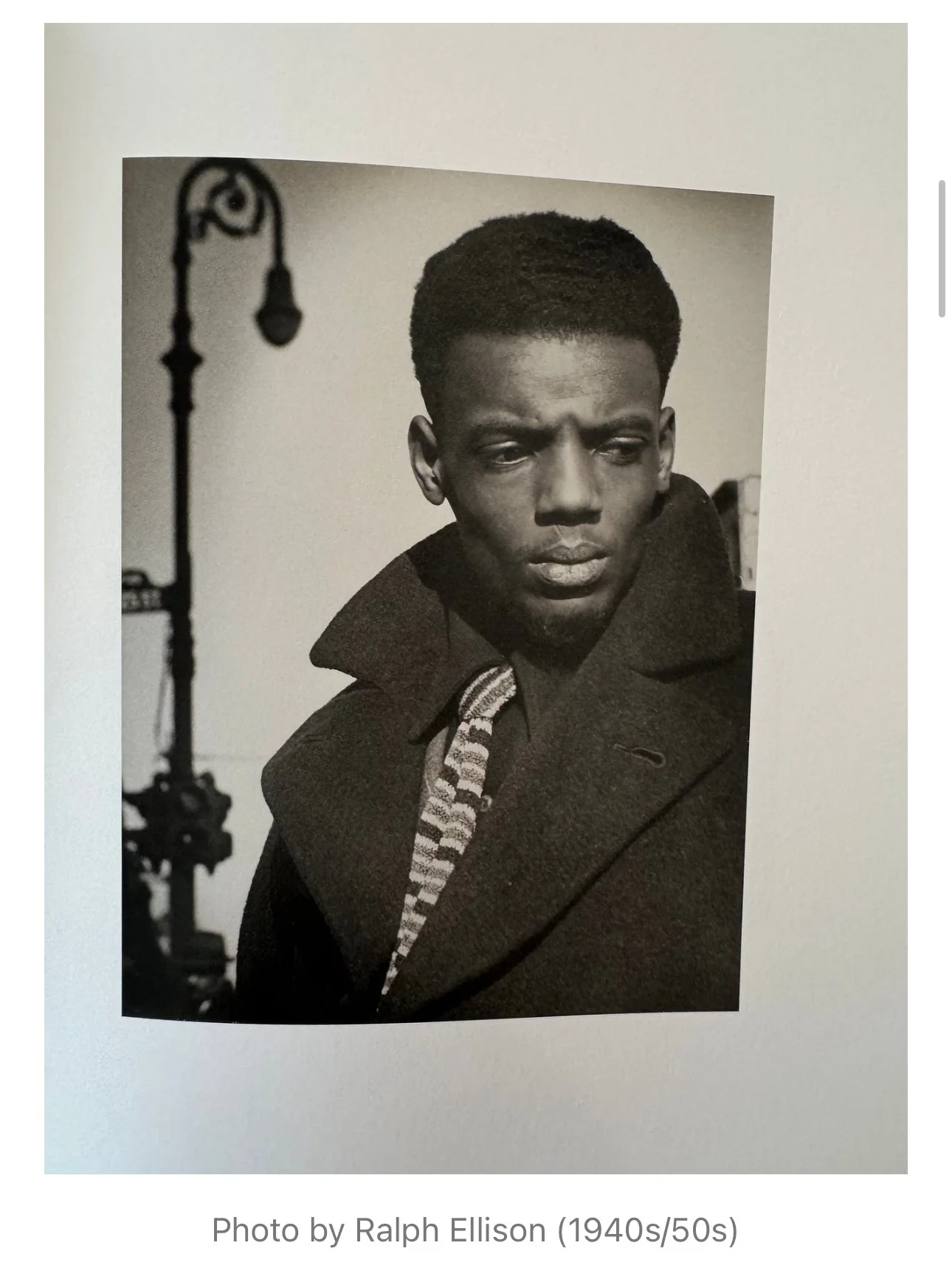

Ellison achieved acclaim in literary circles, but what’s less widely known is his photography. He was fascinated by Black American identity, visibility, and the stories embedded in daily life. Photography became another medium for him to explore those themes. He wasn’t casual about it either, he studied the technical aspects and even built a darkroom in his home to develop his own images.

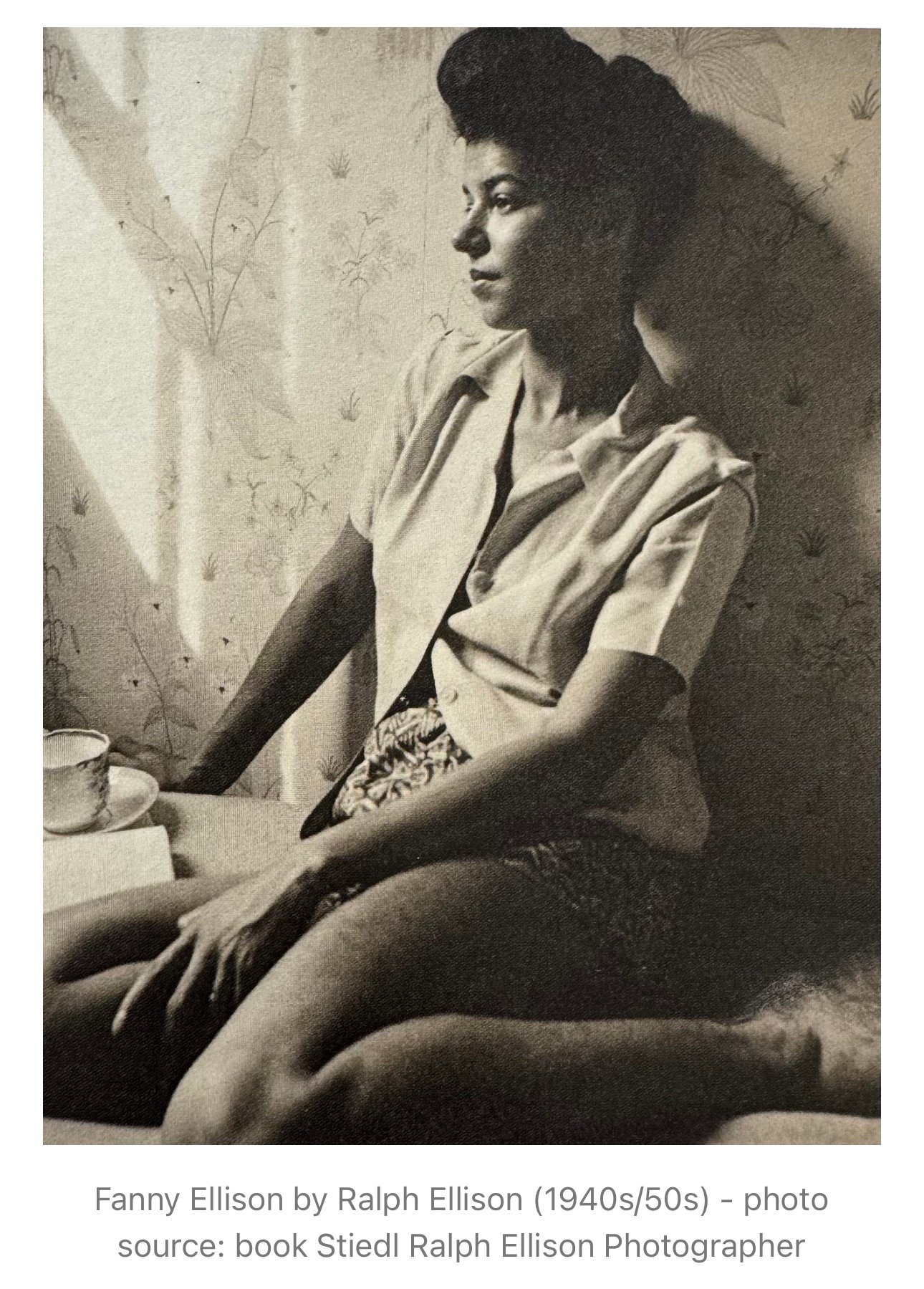

He often photographed his wife, Fanny Ellison, in quiet, domestic moments. These are some of my favorite images of his. She’s simply being at home. I find the simplicity of the images stunning. They aren’t overly posed; they feel relaxed and we get to see images of a Black woman in the 40s and 50s just being casual, in the moment and a muse for her husband.

Each time I research artists and writers from the Harlem Renaissance and beyond, I almost always discover that they took a formative trip to Europe. And when they returned, their work often reflected a renewed sense of purpose.

Poet Langston Hughes traveled extensively in the 1920s, including time in Paris and Spain, where he connected with other Black intellectuals. James Baldwin famously left for Paris in 1948. Barkley Hendricks traveled to Europe in the late 1960s, visiting Italy and the Netherlands, where he encountered classical art that would profoundly influence his iconic paintings.

Ralph Ellison followed a similar path. In the 1950s, he spent time in Rome immersing himself in European art.

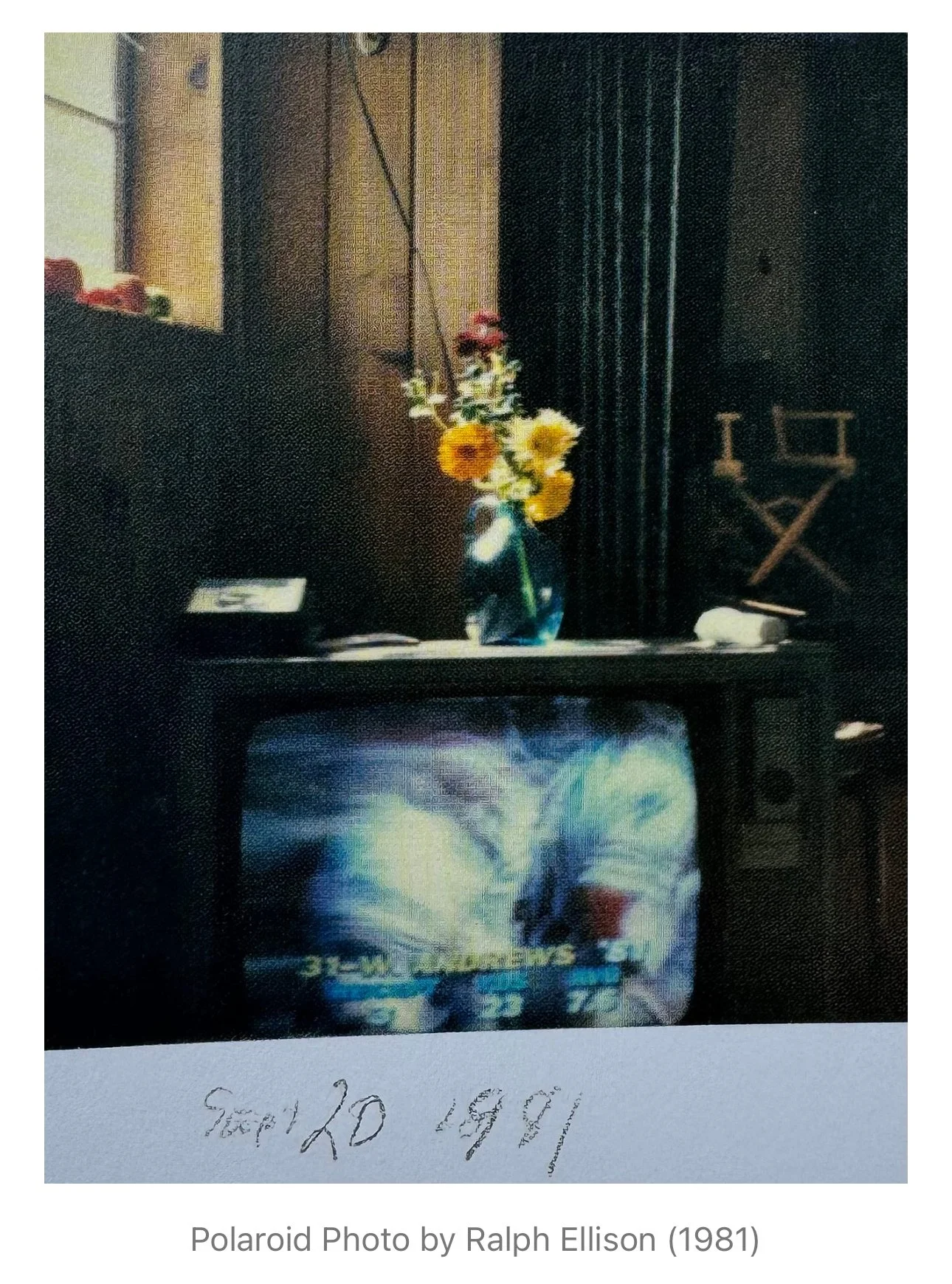

By the 1970s, Ellison had taken to using a Polaroid camera regularly. I love these later Polaroid photographs—still lifes, flowers, simple meals. They offer a quieter look into his world. There’s something intimate about them. I enjoy images like these because they’re not meant to be deep or historical, they’re simply a man appreciating the composition of a flower or the food on his plate which all feels counter to how he was likely expected to see the world.

In learning about Ellison’s life as a photographer, I’m reminded that whatever your main creative pursuit may be, it is important to look up and around to notice the artists in your circle exploring other lanes and learn from them. Ellison was fully immersed in writing when he connected with Gordon Parks in the 40s—then an emerging photographer—who would go on to become the first Black staff photographer at Life magazine and a prolific venerated visual artist.

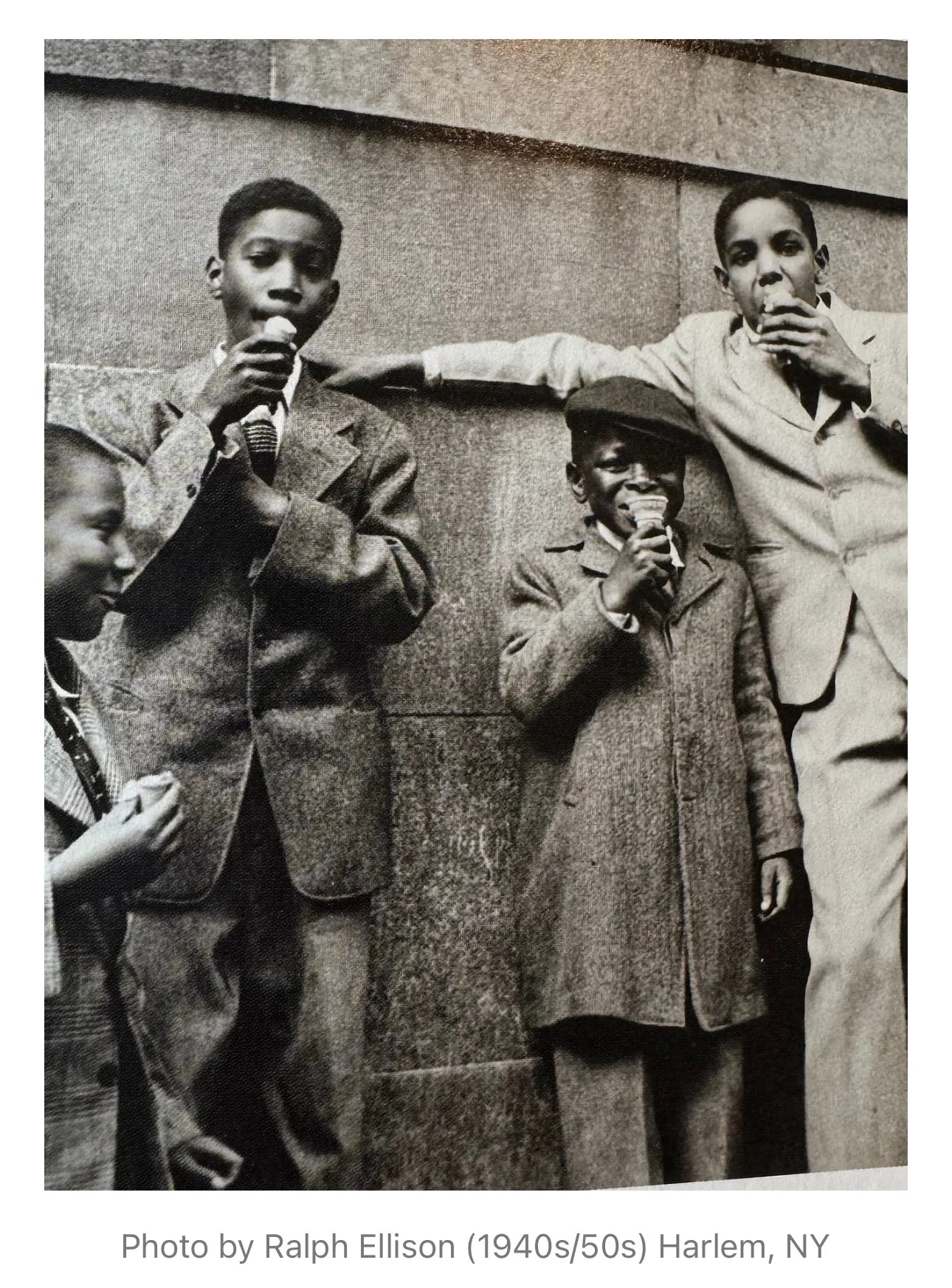

The two men would walk the streets of Harlem together, capturing people and moments. I like to imagine this visual, two creative giants simply taking pictures, following their creative nose and then each returning home to hone his craft, whether it was writing for Ellison or developing film for Parks.

They likely had no idea their work would one day be studied, cherished, and serve as important historical documentation. And yet, they showed up—despite the backdrop of World War II, the struggle for civil rights, Jim Crow, and the everyday demands of life.

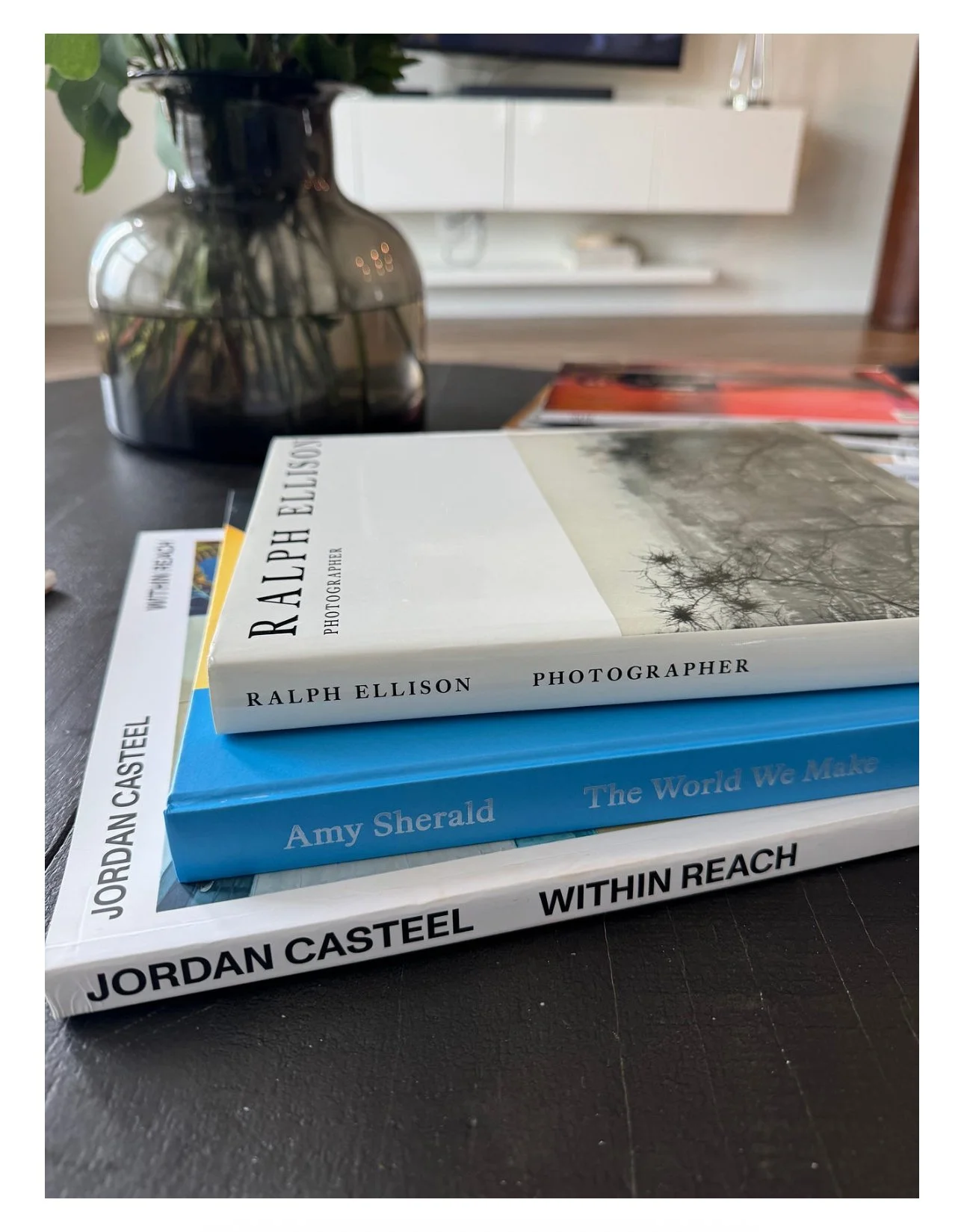

Flipping through my book on Ellison’s work, I am reminded to pull out the Polaroid and camera this summer often and simply document.