Collecting a Meaningful Work of Art

One of my New Year intentions was to invest in a significant piece of art—large in scale, something that wowed me/made me feel an immediate reaction to it, and work where my financial investment goes directly to the artist.

I spent most of the year following several artists on my IG art page, visiting their pages often to see how they were working and evolving.

One artist I kept returning to again and again was Barry Yusufu (Nigerian b. 1996).

Last month, I reached out to him directly to ask about available work. He sent a small catalog, and one piece stayed with me. I told him I’d take a month to sit with it. I wanted to be sure I wasn’t making an impulsive decision.

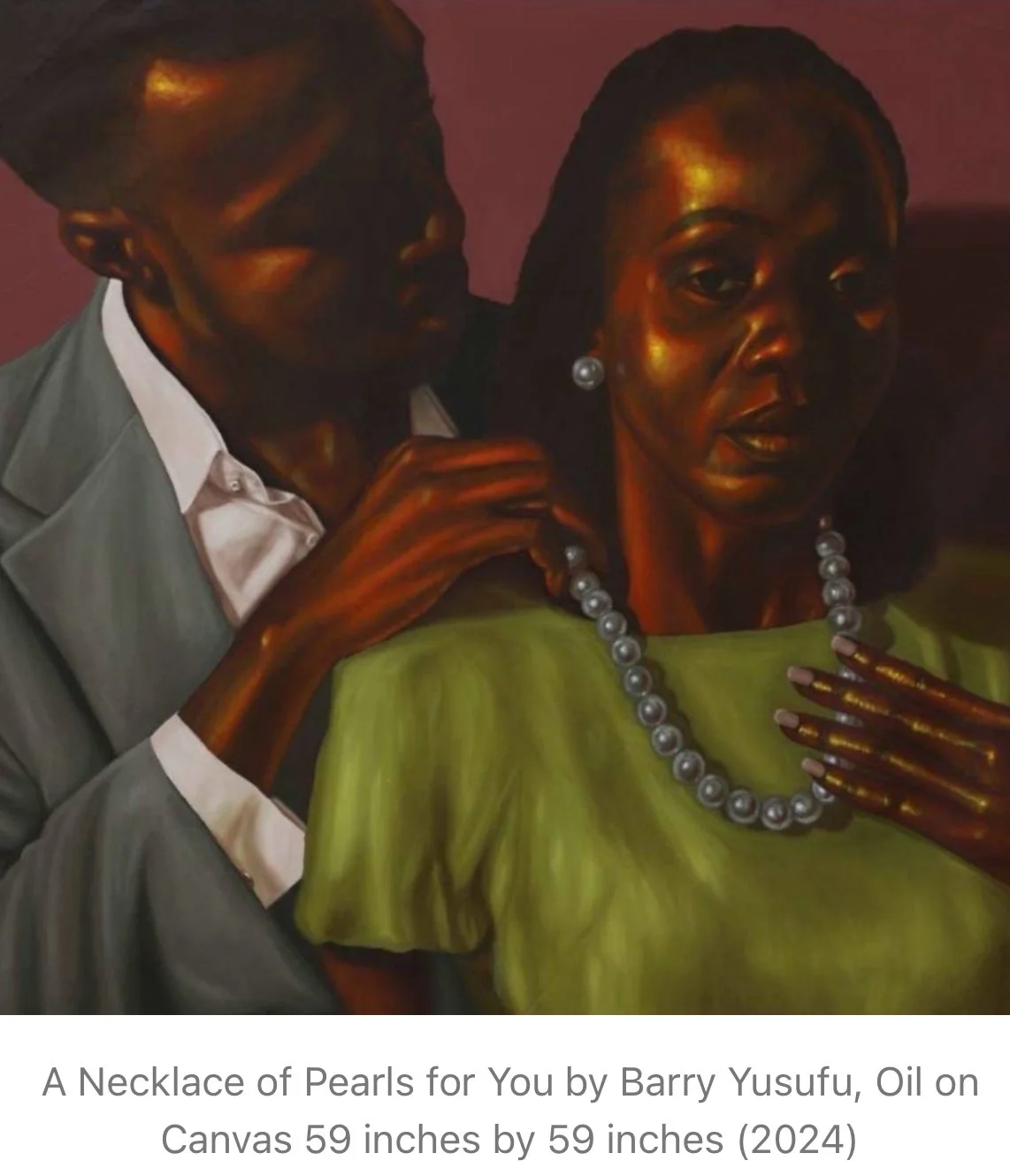

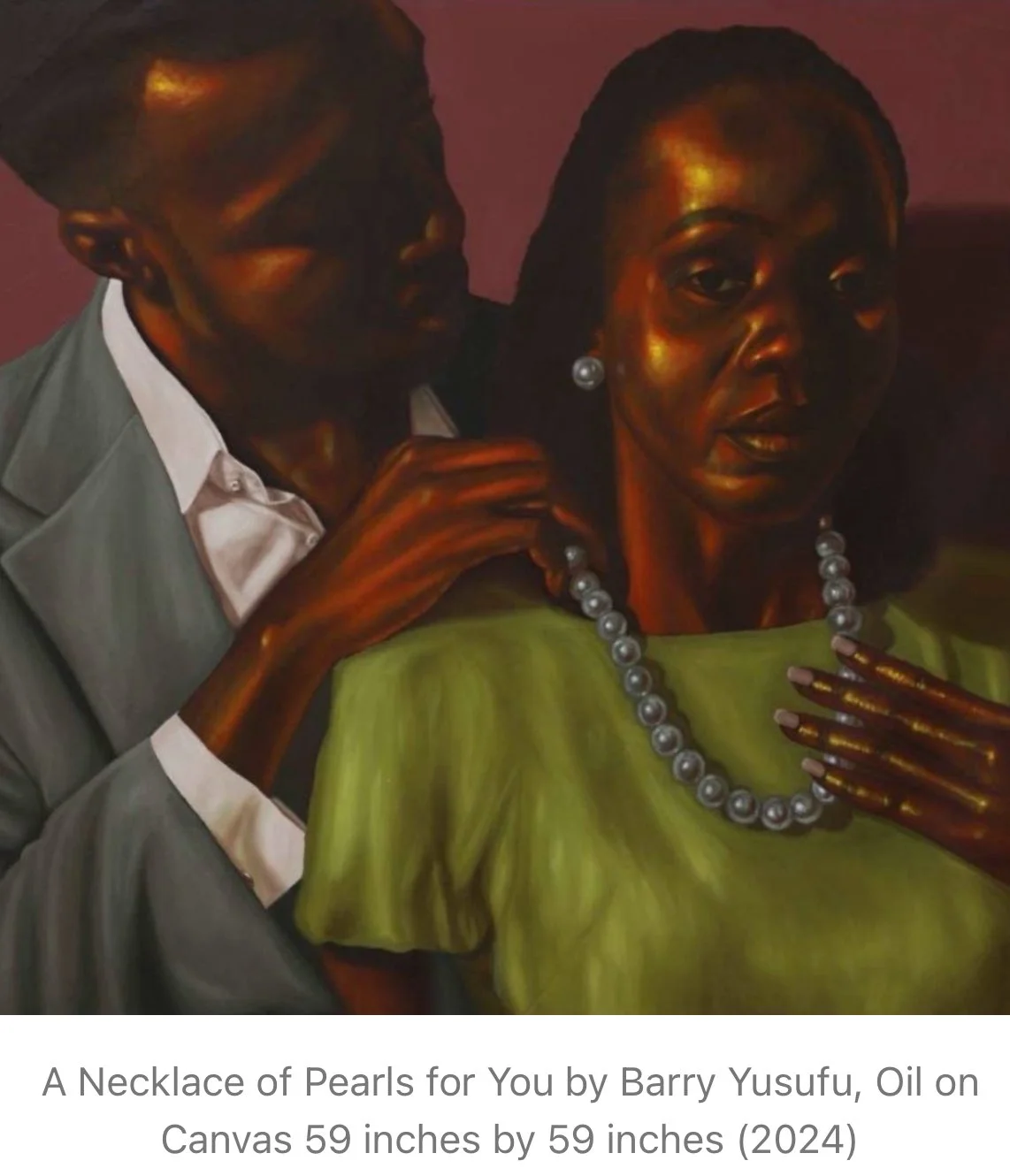

A month later, I still wanted the piece. So I reached out again and moved forward with the transaction. It arrived this week, and I am glad I trusted myself. Below is the piece that’s now part of my art collection.

On top of being absolutely gracious and getting the artwork to me from Nigeria to the U.S. in a matter of days, Barry also agreed to do an interview with me.

Barry and I talked for nearly two hours and easily could have gone on much longer. I found him to be a thoughtful speaker and thinker, an attentive observer of life, people, and society.

He speaks with care and without airs, and he was generous with his time and present with his attention, as if our conversation was his only to-do.

I asked Barry to share a bit about his background and upbringing. He grew up in a small town called Keffir in Nigeria, where everyone knows each other. He described the town as super humble and not a place where people can dream or imagine; however, he and his siblings were raised to dream.

When speaking about his mother, it was clear that his confidante was his mother. I found it endearing when he told me she often referred to him and his siblings as her “angels.”

I had read that Barry was a self-taught artist, so I asked him about this. I was expecting to hear a familiar story about a child who often drew and always wanted to be an artist. Instead, Barry shared a story about following an unexpected opening.

That opening arrived after he pursued a traditional educational path at university in Nigeria from 2014–2016 but was unable to finish his program due to financial constraints. He went on to work at a restaurant to make ends meet, only for the restaurant to burn down.

Burnt out and lonely, Barry drew a picture of his then girlfriend. She was stunned by his work.

Barry began to draw everything around him. Prior to this time, he recalled drawing his parents a bit when he was a child, but he never really drew consistently. After gifting his girlfriend the portrait, he began to wonder if he could pursue art and decided to step into this opening.

Around this time, in 2017, he discovered artists on Instagram and connected with an artist who encouraged him to join an art group in Abuja, Nigeria. Barry barely had enough money for transportation to Abuja to meet with the group, but he scrambled some money together and went anyway.

Meeting this community of artists was a turning point for him. The artists he met were painting large-scale works, wholeheartedly pursuing their art dreams, and leaning on one another. It inspired Barry tremendously.

He returned home committed to his craft, starting with drawing in pencil and then moving on to acrylics and charcoal.

Between 2018 and 2019, he kept painting and creating and participated in over 20 exhibitions in Nigeria; however, it was difficult to sell his work because he felt that most collectors there rarely wanted portraits of strangers in their homes.

Then one day, a curator in the U.S. reached out to him to participate in an exhibit in NYC. He shipped several works to her in the U.S.

He had no idea how to price his work for an international audience or whether it would sell. To his surprise, all of the work sold, which gave him a boost and affirmation in the international art world.

I wanted to know more about Barry’s art technique, so I probed him about that. His response was yet another example of how Barry allows himself to experiment and discover.

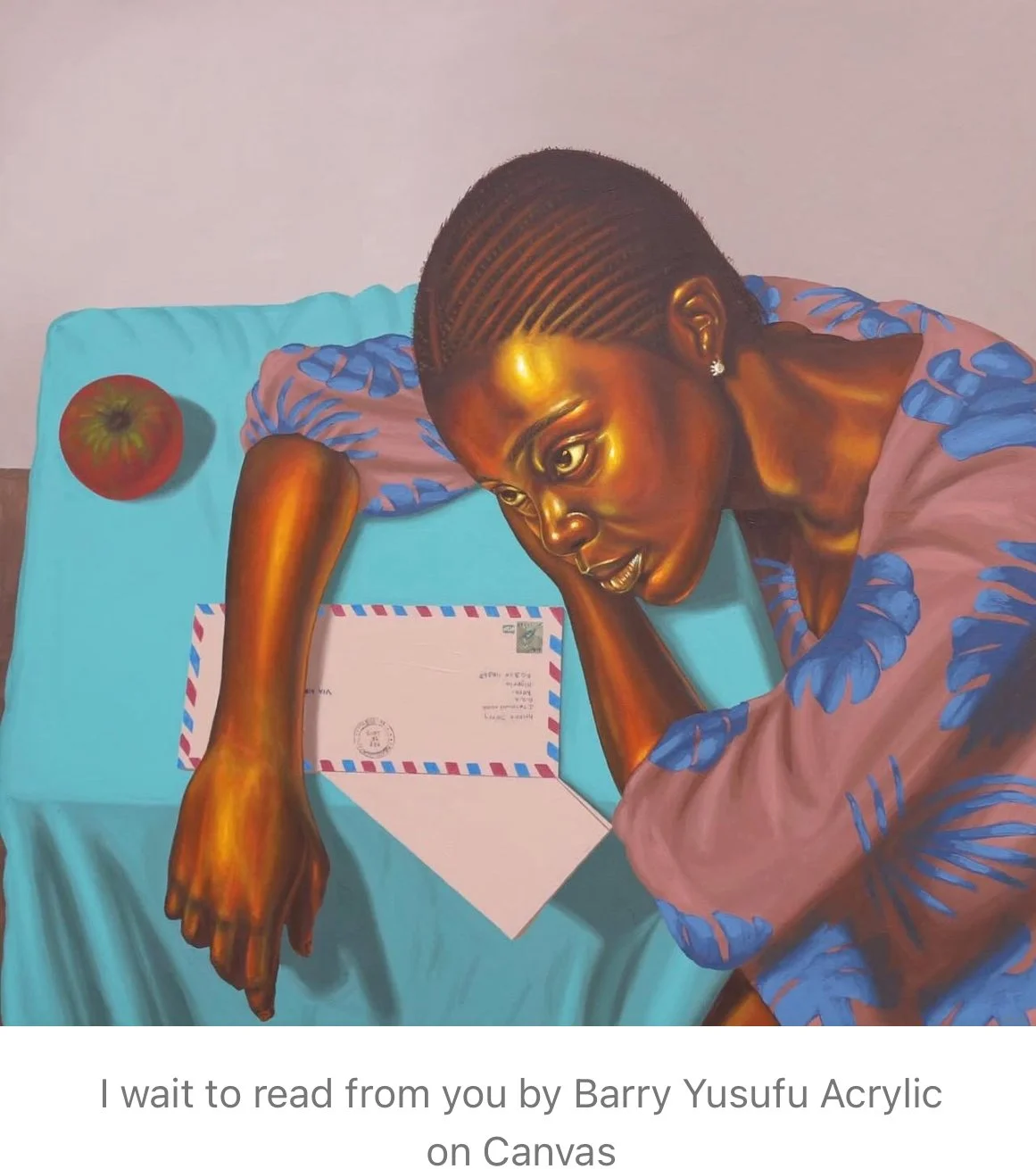

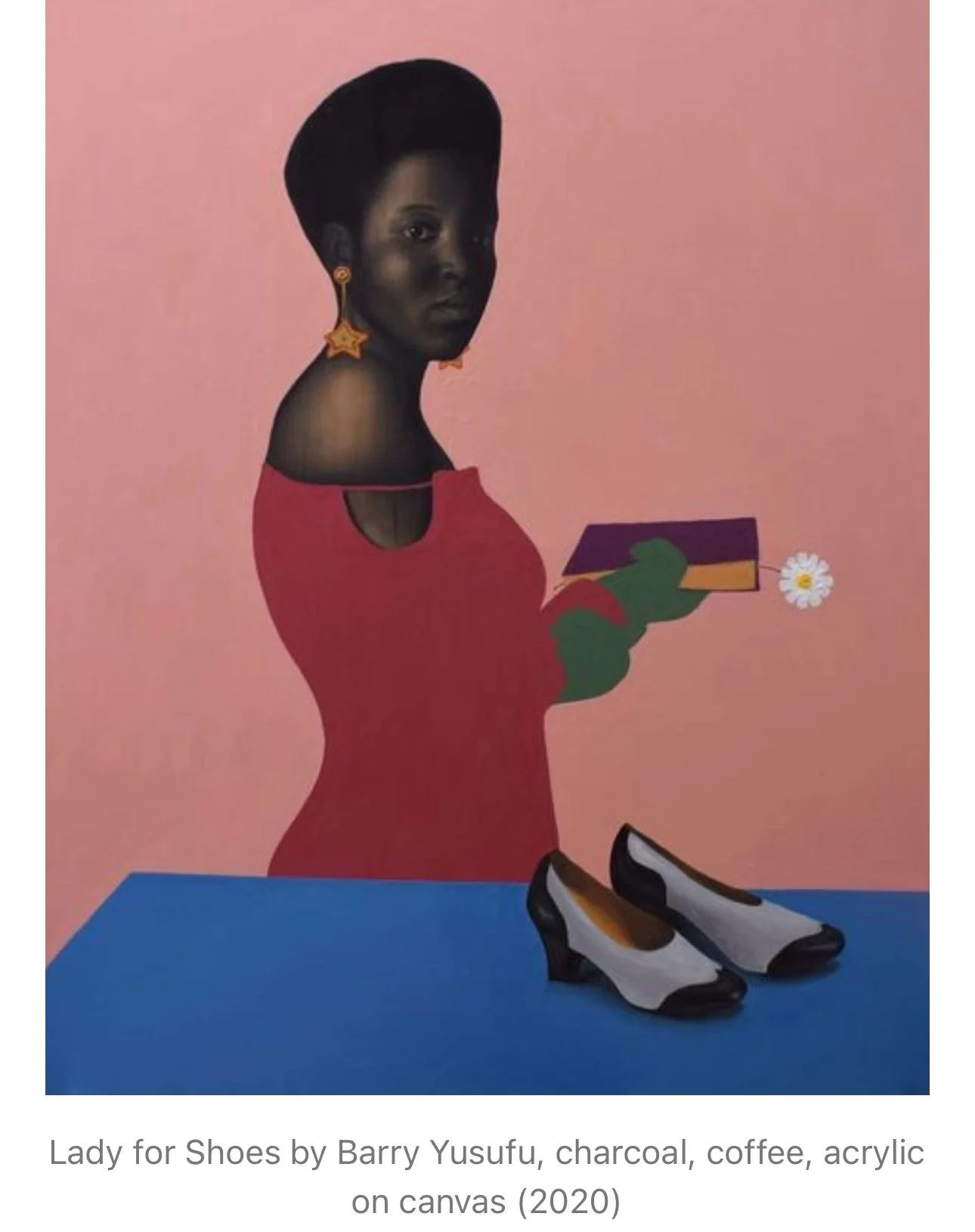

He shared that he was working on a piece and didn’t have enough paint for the negative spaces, so he decided to experiment and mix coffee with charcoal. The result was a beautiful, rich, smooth surface.

This technique caught the attention of Ghanaian artist Amoako Boafo, whose artwork sells for upwards of a million dollars, and led him to purchase one of Barry’s artworks.

Barry went on to create a series of works using this method, and many people began to see it as his signature style.

His work caught the attention of a gallery in Italy that wanted to do a solo exhibition of his work. They were interested in exhibiting his charcoal, coffee, and acrylic technique, but Barry wanted to do something different.

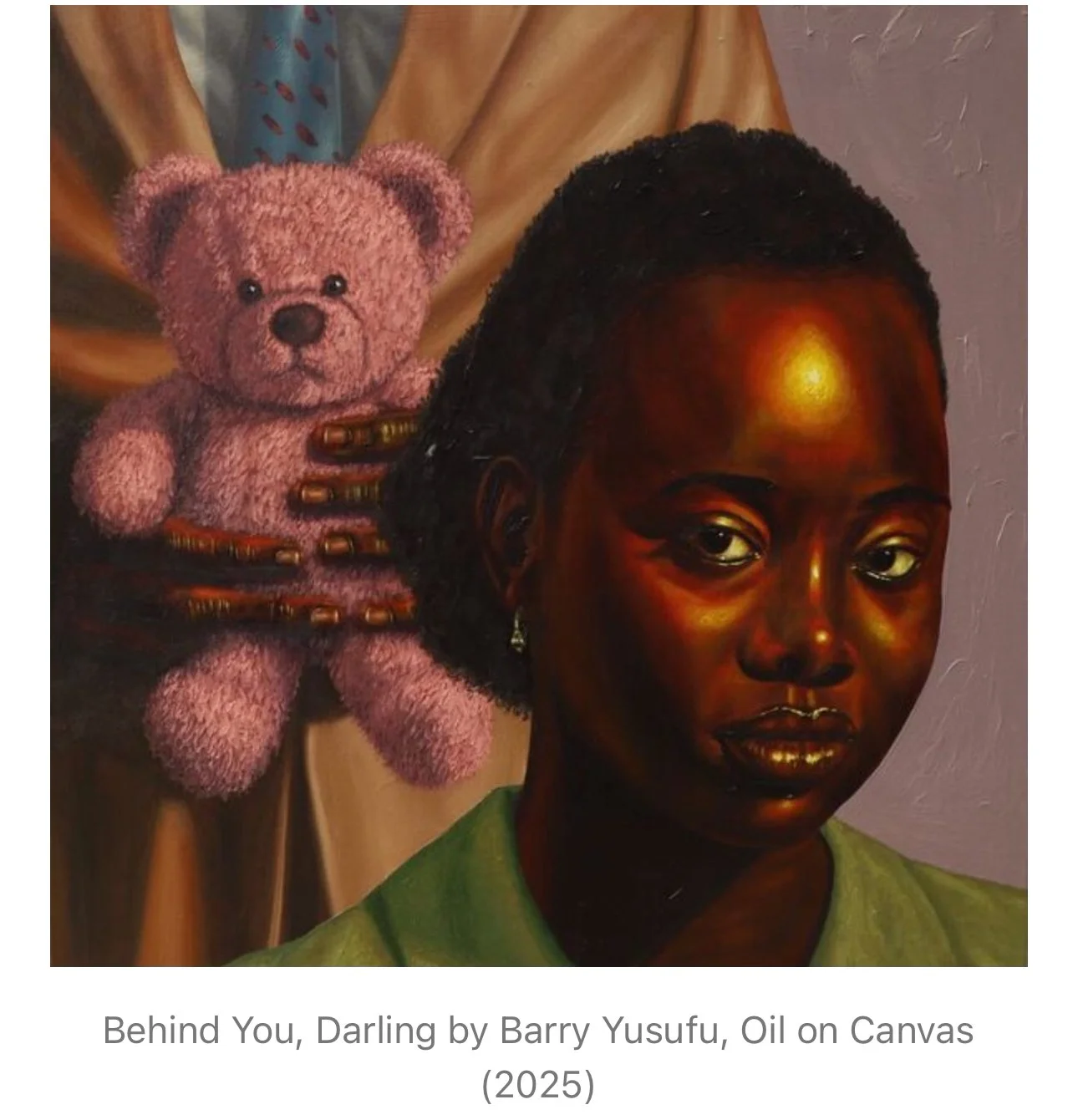

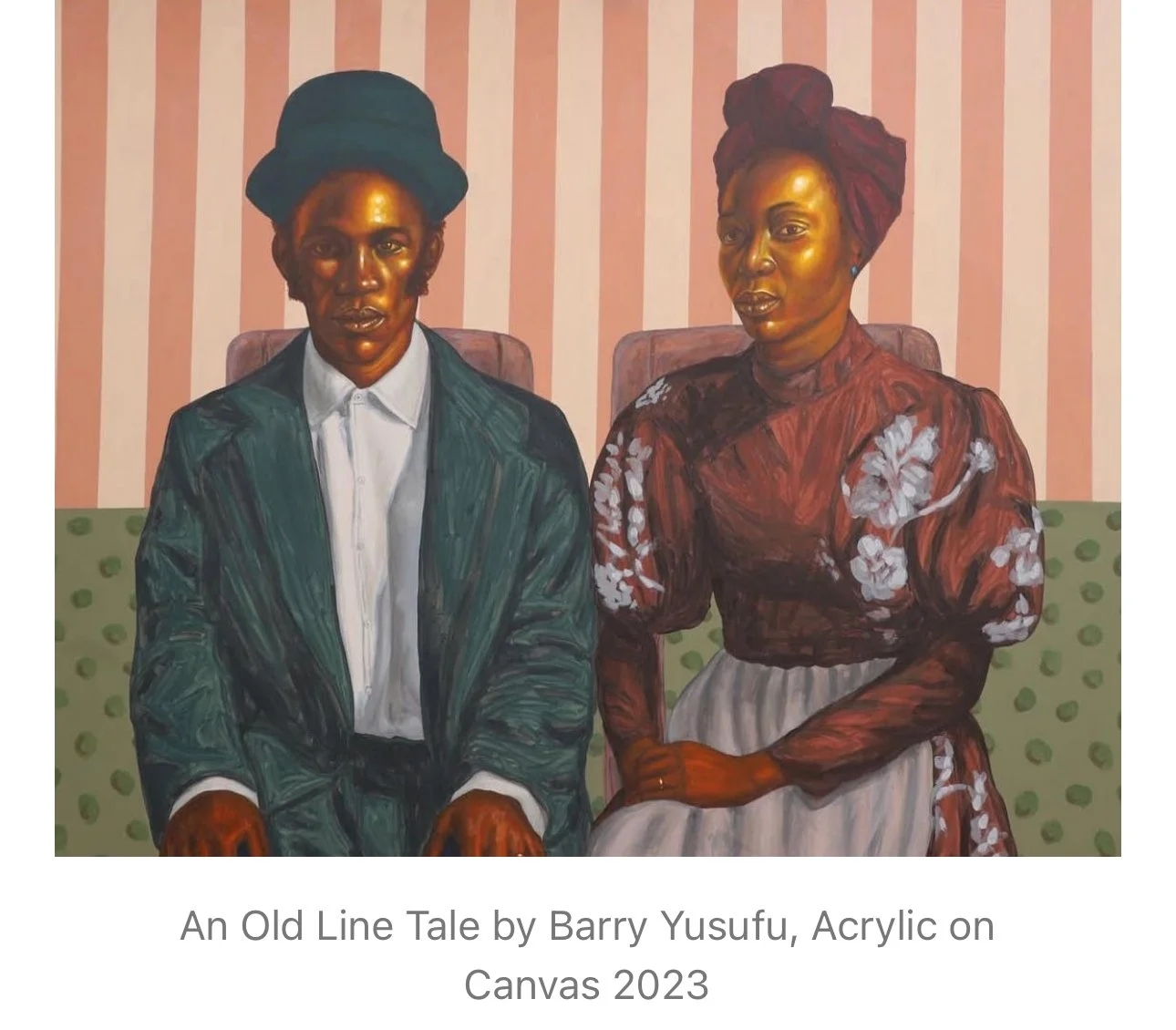

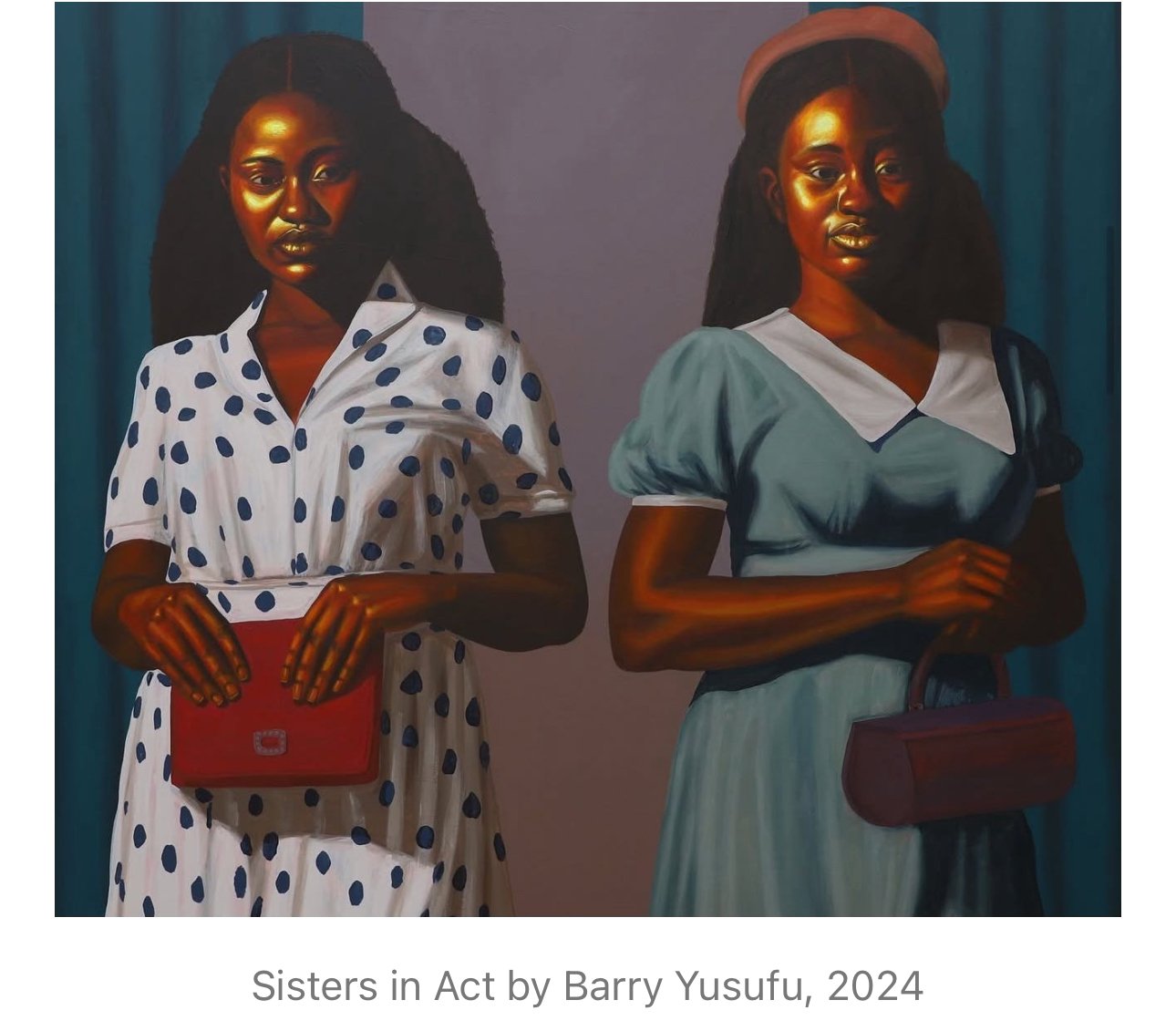

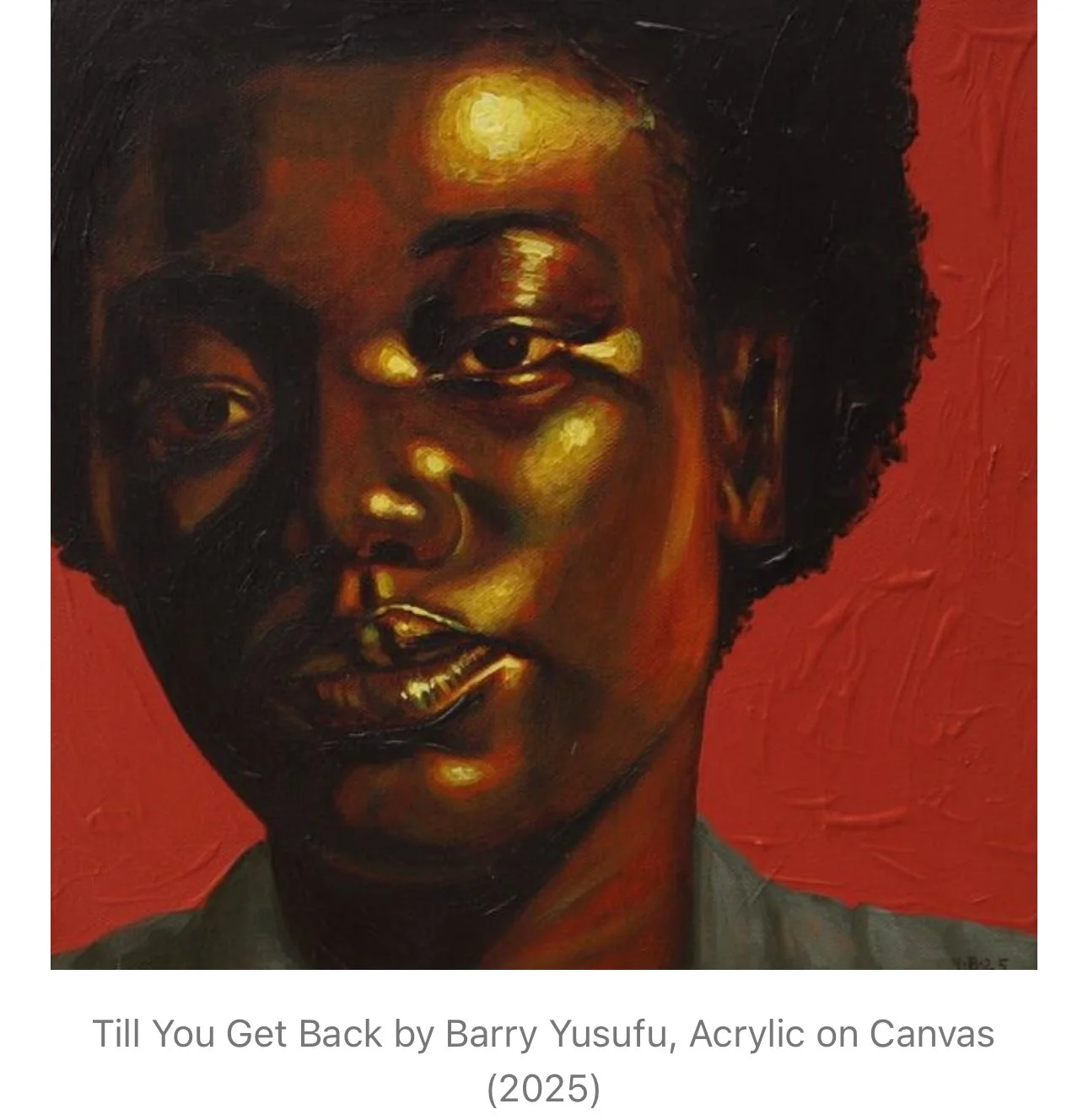

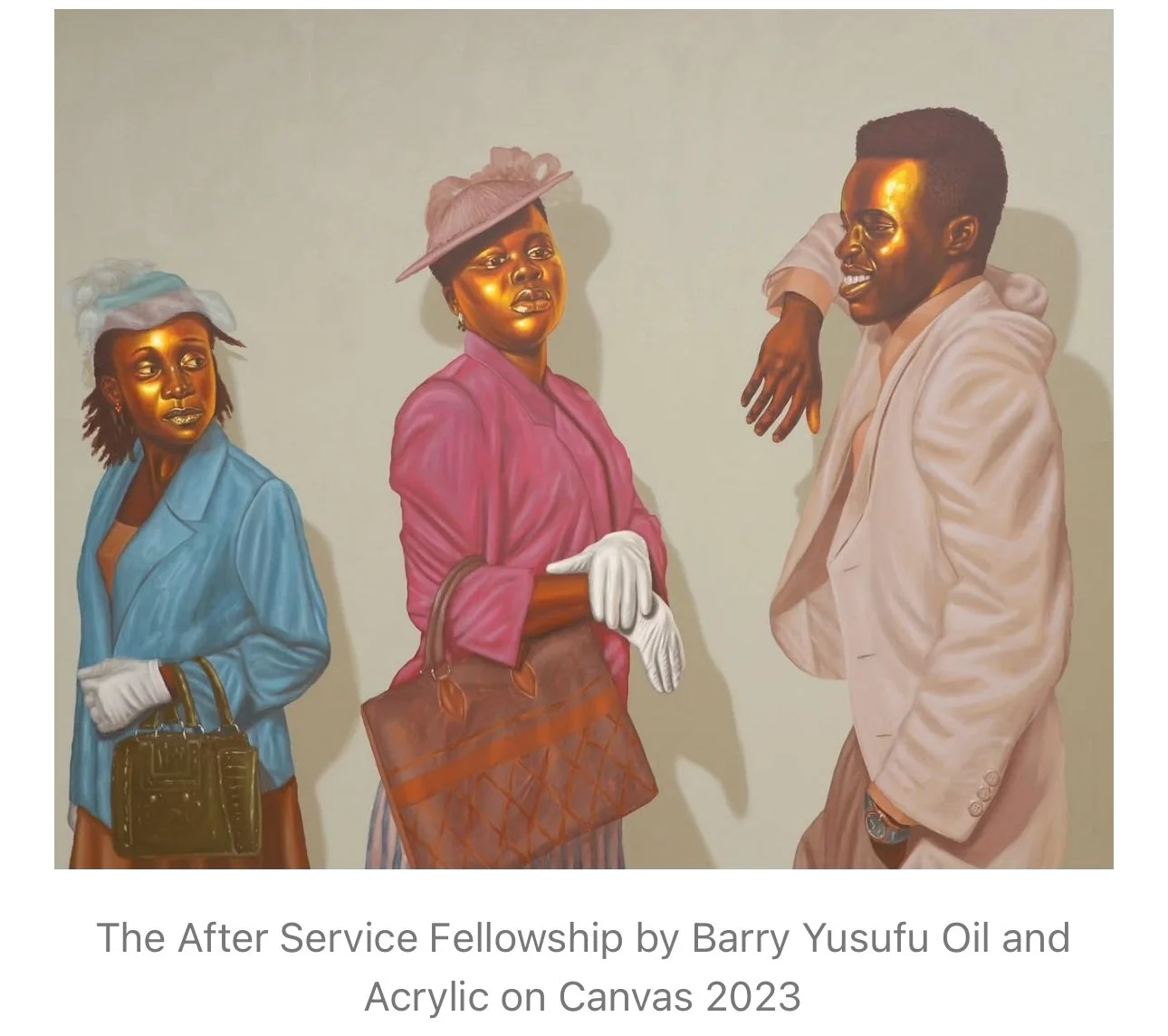

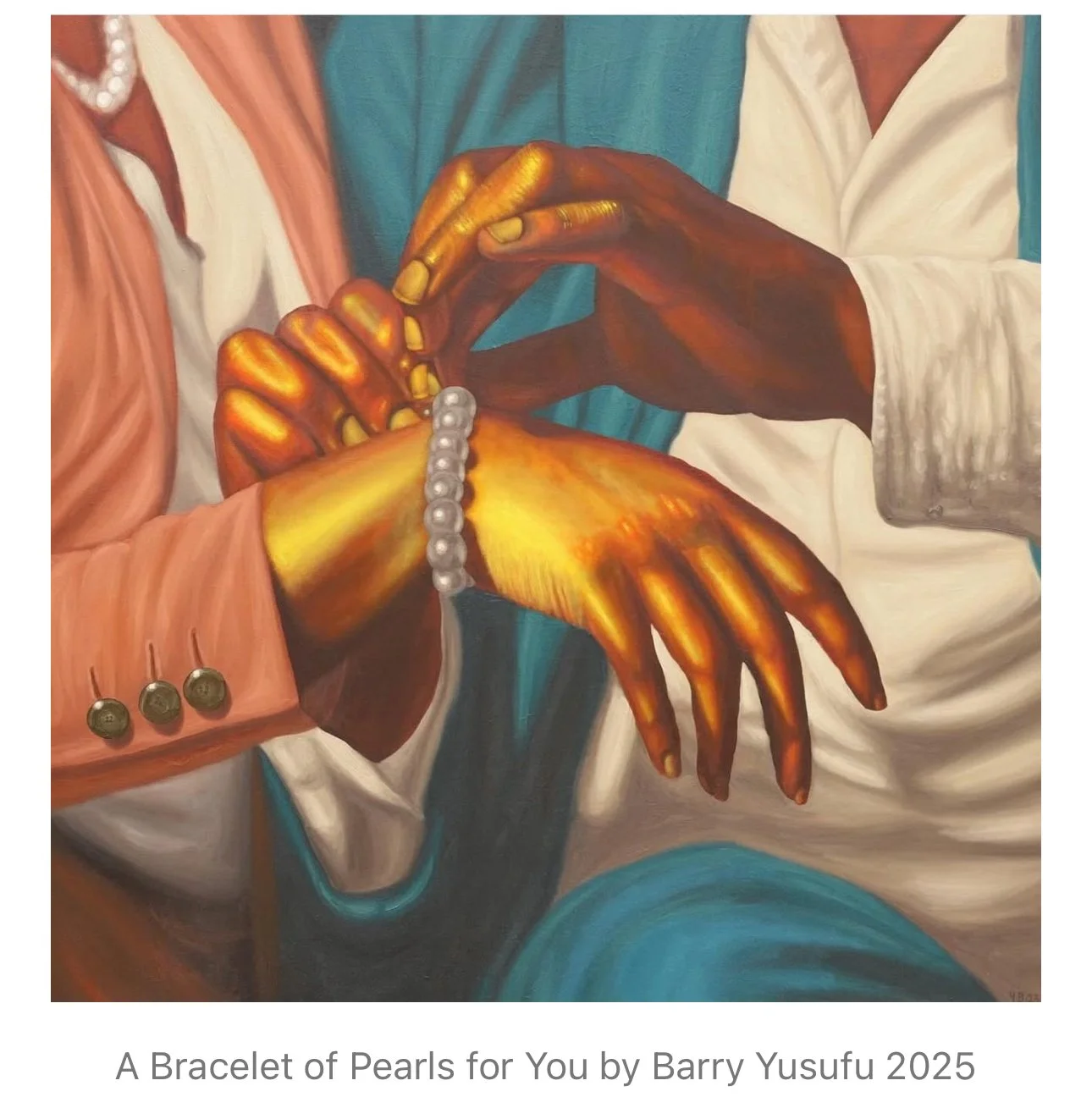

During this time, Barry ran out of paint and only had raw umber, yellow, orange, black, and white paint on hand. He began to experiment with what he had and discovered he could create bronze, alloy-like skin tones that seemed to glow off the canvas. He knew immediately this was how he wanted to represent the people he painted.

This discovery reminded him of how Jesus is described in the Bible—“skin of bronze.” He also connected the bronze-like skin to how Africa is blessed with raw materials, rich in natural resources. He wanted to move beyond painting Black people solely with charcoal and coffee and instead show the richness of bronze skin.

The gallery in Italy didn’t immediately buy into his new vision, they wanted him to stay with the style they were accustomed to, but Barry stood his ground. He shipped the work to Italy. The exhibition was overwhelmingly well received, and the pieces sold out. It was a surreal moment for him.

At this point of our conversation, I was reminding myself of the importance of trusting the voice inside that gives you a nudge on where and what to do next.

As an artist who was still building his name, it would’ve been the path of least resistance to offer the gallery in Italy his tried-and-true recipe for success, but Barry knew it was time for him to take his work to the next iteration, and he listened.

Barry is currently completing his Master’s in Fine Arts at the University of the Arts of London, ranked second in the world for Art and Design. He is fully funded and moved there from Nigeria in 2024.

I asked Barry why he decided to pursue a formal art education even though he was already a practicing artist, with his work sold to the likes of singer Alicia Keys and her husband Swizz Beatz, and his work held in museums and permanent collections globally.

Barry told me, very plainly and eloquently, that for some artists with privilege, they can pick up an old mattress, call it art, and it will land in a prestigious gallery or museum. But for us, he said, we have to do what we can to remove any possibility of doubt in our abilities.

With the MFA, he wanted a kind of insurance, so no one could deny him a residency, a museum opportunity, or access to certain spaces by saying he didn’t have the credentials to be in the room.

I also got the sense that Barry is someone who is very curious and enjoys learning and discovering new things, so art school, I suspect, is offering a container to explore and grow.

I ended our conversation by asking about the artwork I had purchased—the piece that brought our paths together. I teased Barry, telling him not to ruin my interpretation, then shared what I saw and asked if I was close.

I told him I read the work as broken promises, perhaps by a lover or a son. The woman appears apprehensive about receiving the pearls, a little forlorn. I asked, wistfully, if I was right.

Barry chuckled and said, “All of that is true—and not true at all.”

He explained that he allows viewers to enter his work with their own reflections, but he shared a bit about his intention behind the series. The series is titled In Loving Memory of Love.

While making them, he was thinking about what is lost. No matter who you are, he said, “you know what it feels like to be loved, supported, and to give love. These days, love feels distant, almost dead, and we’ve forgotten what love is.” He wanted to create a window, an opening, for people to reconnect with the idea of love at a time where it feels scarce.

His response made me love the work even more. In a year and a time when we are trying to reclaim love for ourselves, for others, and for our neighbors, and reorient ourselves toward what matters most, toward more human connection and understanding, this work will be a reminder in my home.